This article is part of a semi-monthly column on the history of roleplaying, one game company at a time. The intent is to step back and forth between larger roleplaying companies and smaller, related ones. In a previous column I covered Chaosium. This related article discusses Pagan Publishing, Chaosium’s most notable licensee and for a time a hotbed of creativity and originality in the gaming field.

This article was originally published as A Brief History of Game #6 on RPGnet. Its publication preceded the publication of the original Designers & Dragons (2011). A more up to date version of this history can be found in Designers & Dragons: The 90s.

There’s a common entry path into gaming publishing that goes something like this:

A group of gaming enthusiasts decide that they’re going to publish a gaming magazine. They put out their first issue, and it gains some acclaim, and so they continue publishing. But, after they have a few issues under their belt, they realize that this publishing thing is pretty easy, so they put out a game supplement too, possibly drawing upon material originally published in their magazine.

The gaming supplement does even better than the magazine itself. It’s easier to produce, and it nets even more acclaim. Better, especially in those days before d20, the supplement goes into backlist which means that it continues to sell in game stores well past its publication date, whereas the magazine only sells as frontlist in the game store, with each new issue replacing the last one.

After a bit the enthusiasts realize that they can create a much more viable and fulfilling business selling supplements. The magazine slowly gets cut down, appearing semi-yearly or yearly, or is even discontinued entirely. Game supplements are now the company’s bread and butter, and the magazine that got them started is all but forgotten.

We touched briefly upon this pattern when looking at Paizo Publishing, but Pagan Publishing is our first actual example of the pattern at work.

The Unspeakable Oath: 1990-2001

Pagan Publishing was founded in 1990 in Columbia, Missouri. At the heart of the company was John Tynes, who was 19 at the time. He had a love for H.P. Lovecraft and also for Robert Chambers. He was also “going a little crazy”. In an editorial in 1994 he wrote, “The creative work I did then was so intensive and so exciting that, four years later, I still haven’t finished mining the vein I first opened back then. Though it drove me mad for a little while, when I came back I at least had something worth going mad for.” Which all seems like entirely fine credentials for the founder of a Cthulhoid company and perhaps explains some of the energy which would later light up the Cthulhu field.

Much of the rest of the early Pagan staff was a who’s who of gamers from Columbia. First and foremost was Jeff Barber who’d collaborate with Tynes on early adventures and other games, but other Columbians included Brian Bevel, John H. Crowe III, Les Dean, Chris Klepac, and others.

The magazine that got Pagan Publishing going was The Unspeakable Oath, originally a digest-sized quarterly full of Call of Cthulhu goodness. Issue #1 was published in December of 1990, and made its way into the game trade about 3 months later, when the second issue was published.

The Unspeakable Oath was a solid Cthulhu magazine that perhaps emphasized theme and mood a bit more than the average Chaosium publication of the time did, but it was nothing extraordinary. The first six issues (1990-1992) were semi-professional, with black and white cardstock covers. Writers included several past and future Cthulhu names, including Steve Hatherly, Keith Herber, and Scott David Aniolowski. The adventures, such as TUO #2’s “Grace Under Pressure”, by Tynes and Barber, got some good attention, and the covers by Blair Reynolds were well-executed and disturbing.

The Unspeakable Oath published quarterly through 1992. The magazine upgraded to sturdier covers in 1992, then went to full-color covers and an RPG-book size in 1993, but the frequency also dropped. As we’ll see that’s because Pagan had turned to publishing supplements. The first five full-size issues were published from 1993-1997, averaging just one a year. Then after a four year gap the most recent issue of TUO, labeled “16/17” was published in 2001. Pagan Publishing hopes to get one last “double issue” of TUO out to fulfill old subscription obligations, but that’s still pending.

Pagan would ultimately have a second reason for cutting back their magazine, which isn’t as universal in the industry as the rest of this common pattern: they were paying Chaosium a licensing fee on every product, whether it be magazine or supplement. Thus, even moreso than the average RPG company putting out a magazine, the economics of supplements really made good sense to Pagan.

And starting in 1992, Pagan would publish a few supplements a year for close to a decade.

The Early Books: 1992-1993

Pagan Publishing got into game books the same way that most magazine publishers do. They published some compilations of material from their magazine including Courting Madness (1992), which was an anthology of TUO material, Creatures & Cultists (1992), a reprint of a cardgame that appeared in TUO #4, and The Weapons Compendium (1993), which contained Crowe’s weapon stats from TUO (and a lot of new ones too).

Pagan also started publishing original supplements that year, beginning with Alone on Halloween (1992), a solo adventure. However, the first Pagan supplement which really foreshadowed their later success was Devil’s Children (1993), a book with chapters set in 1692 Salem and 1992 Arkham. By this time Chaosium had already extended the core CoC game in the 1890s and the 1990s, but for Pagan’s first full scenario book to make a one-off stop in a totally different time period was original and innovative.

In 1993, Pagan announced even bigger plans: a new Cthulhu RPG called End Time. They described it in an October 31 press release:

End Time is Pagan Publishing’s first role-playing game. It is set in the year 2094, after the stars have come right and Cthulhu and the other Great Old Ones have risen and laid waste to humanity. It’s a sequel of sorts to Chaosium, Inc.’s award-winning Call of Cthulhu RPG, and is based in the same universe — a universe of cosmic horror, as created by writer Howard Phillips Lovecraft, in which malevolent entities beyond the understanding of humans bring unspeakable terrors to our world.

…

In the End Time game, players take the roles of humans in a makeshift colony on Mars. The group escaped the devastation on Earth and fled to the red planet, where a scarce 1200 people comprise the future of the human race. The Earth they left behind is a mystery; the last few decades saw rising madness, horror, chaos, and destruction as had been foretold in eons past.

However, Pagan was just on the edge of big changes that would throw all plans up in the air.

The WotC Years: 1994-1995

In May, 1994 John Tynes took a job with Wizards of the Coast, who was really pushing into the RPG industry now that they were flush with Magic: The Gathering money. On the cusp of moving to Seattle, Tynes had big plans for Pagan. Dennis Detwiller, Brian Appleton, and John H. Crowe III all agreed to move to Seattle with Tynes. They planned to turn the all-volunteer Pagan Publishing into a real company.

And, the publishing schedule that Tynes announced reflected that. First, he promised a set of three nearly complete publications, including Walker in the Wastes, another book of TUO reprints, and a new issue of TUO itself. For August he forecast an introductory set of adventures called End Time: Glimpses. By December he promised End Time itself, plus a player’s guide and a scenario book. A few other strange books called The Golden Dawn and Delta Green were also listed on the year’s publication schedule, for a total of at least nine publications in 1994.

In March when he wrote that schedule, Tynes probably did not foresee the upheaval that the Seattle move would bring. Pagan had previously had a strong presence in Columbia, Missouri. Many of the Pagan volunteers were still there–and not all of them wanted to move. Jeff Barber and others would leave Pagan as a result. They would go on to form Biohazard Games, whose core game, Blue Planet, would share at least a little inspiration with Pagan’s planned End Time game. The credits from Blue Planet would also be filled with early The Unspeakable Oath contributors, representing those who had been left behind.

Pagan Publishing was officially incorporated after Tynes, Detwiller, Appleton, and Crowe moved to Seattle, but the rest of their schedule didn’t hold up, and in fact Pagan would never become the full professional publishing house which Tynes had envisioned in March of 1994.

Pagan’s own End Time did not come out in 1994, nor would it come out from Pagan in the years that followed. Later Pagan would admit that their End Time project was officially dead, citing the fact that their contract with Chaosium prevented them from releasing a standalone Call of Cthulhu RPG. (Author Michael LaBrossiere would eventually release it as a Chaosium monograph a decade later.)

Other than two issues of The Unspeakable Oath and that book of reprints, Pagan Publishing would only manage two supplements over the next year, Walker in the Wastes (1994) and Coming Full Circle (1995), both by John H. Crowe III. The first was a massive Ithaqua campaign, and the second a set of linked scenarios. Both unusually pushed the standard 1920s setting into the 1930s.

Coming Full Circle would mark the last of Pagan’s early supplements. None of these early releases are among Pagan’s top-rated books, with the possible exception of Walker in the Wastes.

However, they did include a few elements which helped them stand out. The grayscale artwork was better quality than most of the Chaosium publications at the time, and the time periods were just slightly varied. Though it doesn’t particularly come across in the printed word, Pagan adventures often made good use of sound effects and other props–which Pagan was able to show off when running their games at cons. For “Grace Under Pressure”, for example, they suggested using three tape decks during the adventure, one containing whale songs, another containing SONAR pings, and a third containing specific radio communication.

Nonetheless, despite small advances like the sound effects, the varied time periods, and others, Pagan really hadn’t done anything to truly distinguish their take on Call of Cthulhu. They were just another licensee publishing modules, as Games Workshop, Grenadier, TOME, and Triad had before them.

That was about to change.

In June 1995 Tynes resigned from Wizards of the Coast, sickened by new corporate ideals of branding. He’d later discuss the evolution of Wizards in his famous article, Death to the Minotaur. It was just as well, because six months later Wizards cut their entire RPG division.

Now, Tynes not only had his focus back on Pagan, but he also brought with him lessons that he’d learned from his time working Wizards, including a new take on graphic design. In the company years, Pagan would publish what are widely considered their best Call of Cthulhu supplements, and the ones that truly marked Pagan as their own company.

The Creative Peak: 1996-2000

Pagan Publishing started its new era by picking up the rights to Jonathan Tweet’s innovative RPG, Everway. The acquisition was announced in a joint press release on March 6, 1996. It gave Pagan a second chance to publish an actual RPG, not just supplements for someone else’s game. Unfortunately, it would never come to fruition. On March 25, 1996 Pagan announced a change of plans, saying that “the company’s goals were incompatible with acquiring Everway”. Instead the rights passed to Rubicon Games.

And instead Pagan Publishing pursued their core business of producing Cthulhu supplements. They had two supplements on the backburner, which Tynes had promised back in 1994: The Golden Dawn and Delta Green. Each sought to solve the same problem, which was how to get characters together in a Call of Cthulhu game, as Tynes would discuss in a later interview:

In the course of playing through Masks of Nyarlathotep and other campaigns, it became clear to me that the biggest problem CoC had was the lack of a credible narrative structure. That is, a reason why a group of people would band together to fight the Mythos. This problem became acute during a campaign, where characters would die and we’d somehow have to justify new characters joining this group of paranoid monster-hunters. I wanted to develop ways to make this work, to provide a structure in which characters could come and go.

The Golden Dawn (1996) solved this problem for the 1890s. It described a Victorian occult society full of period luminaries. Like many of the Pagan Publishing supplements, it dripped with theming and historical detail.

It was also the first truly beautiful Pagan Publishing supplement, featuring full-page bleeds, background textures, and textured maps, all of which combined to give the supplement a highly professional, artistic look that wasn’t common in the industry at the time. It’s likely that Tynes picked up the new ideas for layout from Wizards of the Coast who used some similar styles of layout for their short-lived RPG lines. It wouldn’t be mimicked by Call of Cthulhu core publisher, Chaosium, for a few more years.

But the next supplement was the one that would truly break new ground.

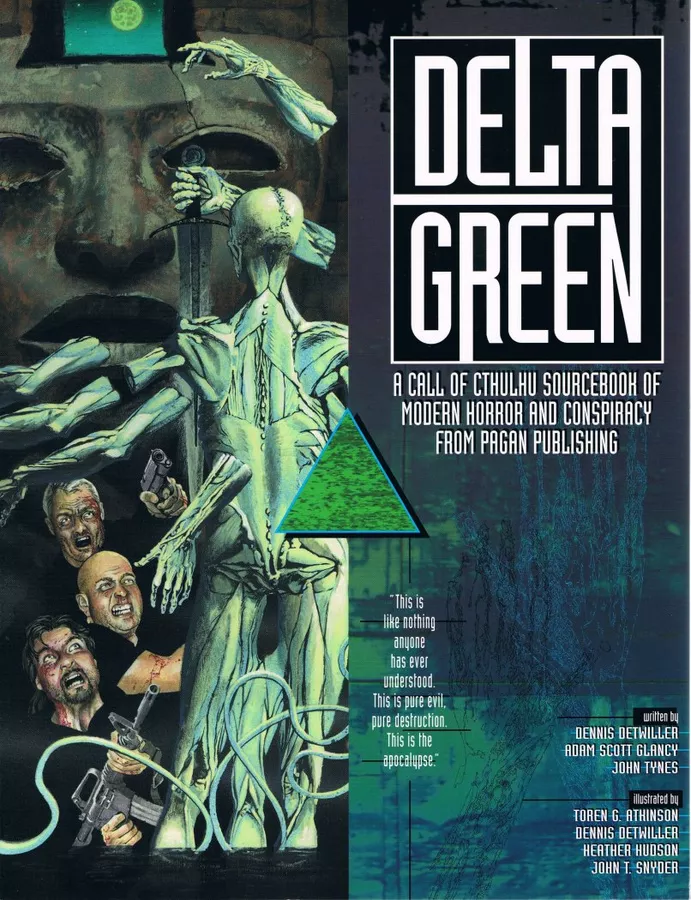

Way back in The Unspeakable Oath #7 (1992) Tynes had proposed a solution for the problem of getting characters together in the modern day. Tynes, Dennis Detwiller, and newcomer Adam Scott Glancy would expand this idea of a secret modern military organization into their other long-promised supplement: Delta Green (1996).

The easy description of Delta Green is that it’s a combination of Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos with The X-Files. And, The X-Files was definitely popular by the time Delta Green was finally released, but that was after many years of development. Delta Green‘s first appearance in TUO #7 actually predated The X-Files by about nine months. It’s a case of simultaneous generation, and a clear indication that the ideas lay heavy upon the human psyche, and were just waiting to be developed.

Years later Charles Stross would write a somewhat similar book called The Atrocity Archives (2004) about a British intelligence agency investigating Mythos-like horrors. He’d say in an afterword to the book: “All I can say in my defense is … I hadn’t heard of ‘Delta Green’ when I wrote ‘The Atrocity Archive’ … I’ll leave it at that except to say that ‘Delta Green’ has come dangerously close to making me pick up the dice again.”

So it goes.

Delta Green merged Lovecraft’s pulp horror with modern conspiracy. It also did another thing which Tynes thought was important: it provided a cohesive and compelling modern-day background for Call of Cthulhu, something that Chaosium had never done despite several books set in the era. As Tynes said in an interview:

Lovecraft wrote about the 1920s and 1930s because that was the modern day for him–it wasn’t a historical period. I think his ideas have enough vitality that they flourish in the light of the present day, whatever that happens to be, and they are important enough to deserve ongoing reinterpretation as time goes by.

Delta Green won the Origins award for Best Supplement in 1996, and the acclaim and interest of many fans. After that Pagan published a few more well-regarded supplements. They maintained the same high standards of artwork and layout and they investigated new eras, from the 1900s to the 1940s.

However, nothing would generate the same energy as Delta Green, and thus several more products were released for that line as well. A series of three chapbooks by Dennis Detwiller (1998-2000) provided additional background, but the best received book was the full supplement three years in the making, Delta Green: Countdown (1999).

A somewhat widely distributed story around the Internet suggests that Chaosium limited Pagan’s publication of Call of Cthulhu books to three or four books a year following the success of Delta Green. And, while Chaosium might have reminded Pagan of such an existing limitation (no doubt going back to the time when Pagan was publishing a quarterly magazine), it’s relatively unlikely that it ever had any real effect. Pagan never put out more than two professional gaming supplements during any year. If you count in magazines, they sometimes got out five books in their first few years, while gaming chapbooks got them up to three RPG publications in 1996 and 1998. However, Pagan probably couldn’t have put out more than four mass-market RPG books in any year even if they’d tried.

Nonetheless this may have been one of the factors in the creation of Pagan’s fiction arm, which they called Armitage House. It published Delta Green fiction and other manner of Cthulhiana. Pagan had been publishing fiction chapbooks for a few years, but Delta Green: Alien Intelligence (1998) was their first professional fiction publication. It and the other Armitage House productions would be free of any Chaosium fees or licensing restrictions.

Further stretching their wings, Pagan Publishing also put out The Hills Rise Wild! (2000), a miniatures Cthulhu game, that might well have been their last notable publication.

Ultimately, the year 2000 would mark the end of Pagan’s creative peak for reasons to be described momentarily. However at its height, Pagan Publishing was arguably much more successful than Chaosium, the actual owners of Call of Cthulhu, in capturing the attention and interest of the most serious Cthulhu fans. Some of this can probably be attributed to Keith Herber, Chaosium’s former Call of Cthulhu line editor, leaving Chaosium behind in the early 1990s, but the vast majority of Pagan’s success can be attributed to themselves alone.

First of all, there’s little doubt that Pagan Publishing managed to gather together a very talented group of individuals. John Tynes is a notable author. At the time of this writing several books that he was involved with hold top-ranked spots in the RPGnet Gaming Index, including: Delta Green: Countdown (#2), Delta Green (#4), Unknown Armies (#5), and Call of Cthulhu d20 (#13). Dennis Detwiller proved that he was likewise skilled with his release of Godlike, which we’ll return to shortly. Meanwhile, both Dennis Detwiller and Blair Reynolds provided Pagan Publishing with high-quality art that truly set it apart from other RPG publishers.

Second, Pagan Publishing was really willing to look in different directions from the norm of the Call of Cthulhu line, and thus they were willing to try bold new experiments. This was seen from early on with their alternative settings, and it really culminated in Delta Green, which managed to make the modern day important in a way that Call of Cthulhu never before had, and which reimagined the Cthulhu Mythos in a very modern, yet still very recognizable form.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, Pagan Publishing had the huge advantage of never actually being a professional publishing house, despite their attempt in 1994. This isn’t reflective of the quality of their publications, which were generally top-notch. Instead it reflects the fact that Pagan Publishing didn’t have to worry about paying the bills. They didn’t have staff, nor warehouses, nor offices. If they wanted they could take a whole year working on a single book, and they often did; if a full-time publishing house had tried the same, they’d quickly be out of business. Years later Tynes would say that he wished he’d set Pagan Publishing up as a non-profit, and that really encapsulates the feelings that the Pagan authors had about making top-quality books–not a living. Any largely volunteer organization, given the appropriate skills and talents (which Pagan had in spades), can easily produce better products than any second- or third-tier RPG company, as a simple matter of economics, and that’s the superior position that Pagan Publishing was working from.

Unfortunately spending years sweating over products for a company that ultimately doesn’t show profit can also quickly turn to burnout, and that too seems to be what happened at Pagan Publishing.

By 2002, all of the original Pagan authors would have largely moved on from the company they founded.

The Time of Transition: 1998-2002

Blair Reynolds, the original inspirational artist behind Pagan Publishing, had left the gaming industry in 1994 due to general discontent. Most of his focus afterward went to his erotic Cthulhu comic, Black Sands. The first issue was published in 1996 and never followed up on. He made a brief return to the industry in 1997, illustrating Biohazard’s Blue Planet (1997), Pagan’s The Realm of Shadows (1997), and the cover to Delta Green: Countdown (1999), which appears to be his last published RPG work. He’d also contribute a story to Delta Green: Alien Intelligence (1998).

John H. Crowe III, one of the most prolific authors at Pagan, published his last book, Mortal Coils, in 1998.

John Tynes had gone to work for Daedalus following his year with Wizards of the Coast. A few years thereafter he put out his first major publication for another publisher, Unknown Armies (1998) for Atlas Games. Another original RPG system, Puppetland (1999), would shortly follow, this time for Hogshead Publishing.

Dennis Detwiller meanwhile was working on a new RPG called Godlike, a superhero game set in the 1930s and 1940s. Tynes had originally suggested its development to Detwiller so that Pagan could finally put out their own RPG. However, this third attempt at an RPG wouldn’t be produced by Pagan either. Instead it would ultimately be published in 2001 by newcomer Hobgoblynn Press–primarily because of Pagan’s very slow production schedule. Detwiller has since formed Arc Dream Publishing, which is putting out additional Godlike projects. His next major book, Wild Talents is due out this December.

On January 1, 2001 John Tynes announced to his partners that he was getting out of the roleplaying biz. He said that he expected to be done with the field by 2002. Adam Scott Glancy, who had joined Pagan to write Delta Green, was named the new president of Pagan, but he inherited a company which had lost most of its creative force.

At the last moment, John Tynes was offered a final hoorah. He was contracted by Wizards of the Coast to write the background material for the d20 version of Call of Cthulhu, which had been licensed to Wizards by Chaosium. Tynes accepted the contract and produced the material with help from the Pagan crew. While writing the book, he continued to try and work against the Call of Cthulhu status quo. In particular, he rebelled against the codification of the Cthulhu Mythos so prevalent in the Chaosium RPG material, and instead tried to imbue the game with a new sense of wonder and horror.

The book was completed in 2002, meeting Tynes’ deadline.

The Modern Age: 2001-2006

Since 2001, Pagan Publishing has put out just four books (including two Armitage House publications): a Delta Green short story anthology; a Delta Green novel; another collection of adventures from old Unspeakable Oaths; and the final (to date) issue of that magazine. The last of these books was Dennis Detwiller’s novel, Delta Green: Denied to the Enemy (2003). Though Glancy stays on as president, the rest of the principals are gone. The majority of their books are out of print, including Delta Green itself.

I’d be tempted to list Pagan as RIP 2003 except for the fact their website remains live and is occasionally updated, and that Glancy continues to say that the new d20 version of Delta Green, now three years late, will be out any month now. The latest word is encouraging: it looks like it’ll be out any month now.

Of course one has to wonder about the utility of a d20 conversion, now that Call of Cthulhu d20 project is out-of-print, with not even Chaosium providing any support for it. Copies of CoC d20 are now selling used for $50-$100, generally underlining the game’s unavailability.

Lately EOS Press, the modern incarnation of Hobgoblynn Press (who changed their name in 2003), has been working closely with Pagan. They put out the newest version of Creatures & Cultists and are listing Delta Green d20 on their website too, with the current status projected as 95% done. I wouldn’t be too surprised if Pagan fades into EOS in the next few years, because if anything the modern age of Pagan shows one thing–that it’s quite hard to run a publishing company on your own, even if you don’t have to worry about professional nuisances like payroll and rent.

Parts of this article are based on USENET postings and info from The Unspeakable Oath magazine. Thanks to Dennis Detwiller, Allan Grohe, and Shane Ivey for looking over this piece. And thanks to Detwiller for additional comments and corrections and to Grohe for some fairly extensive thoughts on Pagan’s early days.