Lion Rampant was a small game company that appeared in 1987. It lasted just three years, and it published less than a dozen items, but in that time it managed to offer several innovations for the industry.

This article was originally published as A Brief History of Game #10 on RPGnet. Its publication preceded the publication of the original Designers & Dragons (2011). A more up to date version of this history can be found in Designers & Dragons: The 80s.

Foundation & Whimsy: 1987

Lion Rampant was founded in 1987 by Jonathan Tweet and Mark Rein*Hagen. They were both gameplayers–Mark was running a RuneQuest campaign at the time while Jonathan was running Call of Cthulhu–and they were both students at St. Olaf’s College in Northfield, Minnesota. Game companies often start at colleges, but this time the college would offer something unique to the company. Lion Rampant was named after the heraldic symbol of St. Olaf’s.

Jonathan initially funded Lion Rampant with an inheritance which went to buying the company’s sole computer: a MacPlus with two floppy drives. In 1987, Lion Rampant was one of the first companies taking advantage of the new desktop publishing trends to publish books that looked much more professional than those put out by new companies just five years before. (Unfortunately they also looked entirely like they were published on a Mac, with the rounded boxes that filled their early releases leaving no doubt to the publication platform.)

As is also the case with many young RPG companies, Lion Rampant was strictly a volunteer organization–but nonetheless it soon attracted many volunteers. Lisa Stevens was one of the first. She’d graduated from St. Olaf’s the year before and had been hanging around running Dungeons & Dragons games since. She had editorial experience, which was definitively needed at the company, and she soon became the company’s tie-breaker, offering the final word when Tweet & Rein*Hagen disagreed.

Other locals who joined the company over the next couple of years include John Nephew, Darin “Woody” Eblom, Nicole Lindroos, and Kirsten Swingle. (Some of them, such as Nephew and Swingle, came from Carleton College, the traditional rival of St. Olaf’s; how they felt about working for a company symbolized by the emblem of their rival is unrecorded.)

The initial goal of Lion Rampant was to create a game that did wizards right, but as GenCon 1987 approached it began obvious that their premier product would not be ready. Rather than rushing it out (a mistake made all too often by RPG companies), Lion Rampant instead prepared an alternative product for GenCon 1987: Whimsy Cards.

In 1987 the storytelling branch of roleplaying design was beginning to develop. There were fewer dungeons crawls, and more plotted and city adventures. Dragonlance (DL1-14, 1984-1986) had kicked off a whole new way to look at epics. Games like Paranoia (1984) and Pendragon (1985) deemphasized characters or further suborned them to plot. Story was increasingly important, but no one had taken the next step and placed stories not just in the hands of the gamemasters but also the players.

Enter Whimsy Cards. The idea was simple: print up a deck of 43 cards (plus a few blanks) where each card presented a distinct story element such as “abrupt change of events”, “added animosity”, “bad tidings”, or “bizarre coincidence”. These cards were shuffled and handed out to players at the start of a game; players would later play one of their cards and describe how it applied to the story. If the gamemaster liked the results, he incorporated the description into the story, otherwise he vetoed it.

The original cards were printed on cardstock so poor that they came to be called “flimsies”. Nonetheless, they were a neat and original idea, one of the first products ever that suggested that players were just as good of storytellers as a gamemaster. They probably didn’t light the industry on fire, but they gave Lion Rampant a product to sell at that first GenCon, and they also put them on the map as an indie publisher of innovative RPG products.

(And, the core idea of the whimsies had legs: Torg (1990) was released with a somewhat similar “drama deck” a few years later, while White Wolf eventually released two decks of next generation whimsies, which they called Story Path Cards (1990); they’ll be discussed further in the next article, on White Wolf.)

Publication & Magic: 1987-1988

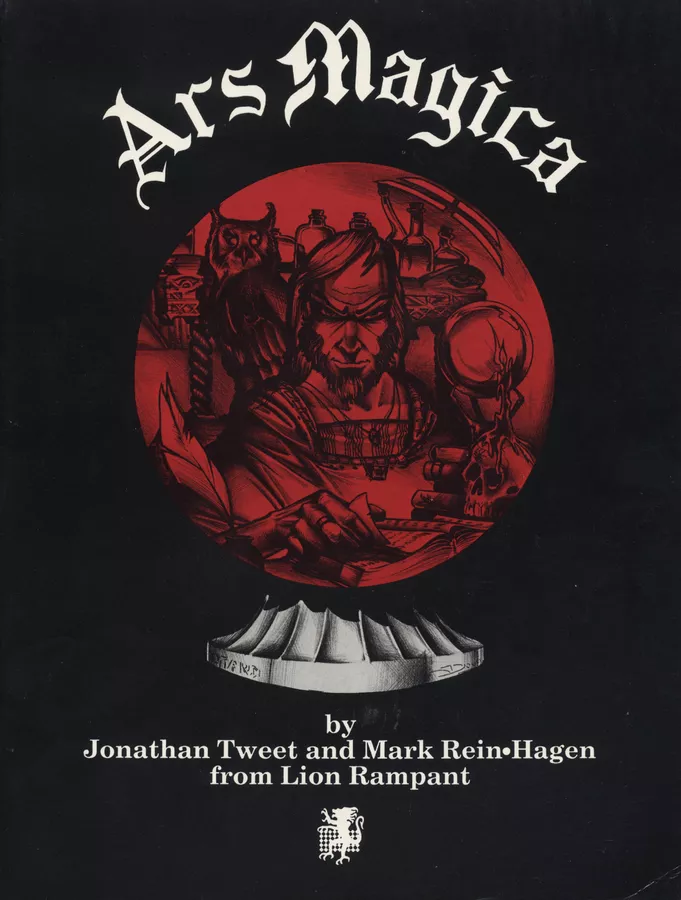

The wizard game which would eventually become known as Ars Magica was in full development by the summer of 1987. Mark Rein*Hagen was offering the wild, imaginative ideas while Jonathan Tweet supplied the careful mechanics. However it still wasn’t ready for publication, and that may well be because Lion Rampant–especially in these early years–was more a bunch of gamer friends who happened to be publishing a product than a professional company.

This was made more clear in late 1987 when some members began to push for Ars Magica‘s publication. Christmas was approaching and there was a chance to catch the holiday sales, but Tweet was intent on perfecting the game whether that resulted in missing Christmas or not.

The game was finally published near the end of the year.

Ars Magica was innovative for several reasons: First was the magic system. Twenty years later it remains one of the most original, innovative, and freeform magic systems in roleplaying. Its base conceit is that all magic is based on five techniques and ten forms. By combining those two elements (e.g., as “Creo Ignem”, or Create Fire) a wizard could generate any type of spell imaginable.

The idea of thematically related spells was not new. Advanced Dungeons & Dragons (1978) had touched upon spell spheres somewhat while Spell Law (1981) had codified similar spells into long lists. However the Ars Magica system took this idea and made it tremendously freeform. Wizards could create any spell based upon their techniques and forms, whether it was in the rulebook or not (and the poor gamemaster just had to figure out the level of said new spell).

Freeform spell casting was complemented by an extensive set of laboratory rules which gave players the opportunity to learn spells, create spells, make magic items, teach apprentices, and create familiars in their off time–and the whole idea of off-time was something relatively new as well. Pendragon (1985) was one of the few previous games which suggested that adventuring was only a small part of a character’s life, and gave rules for what he did the rest of the time.

Second, Ars Magica stepped away from Tolkien fantasy and instead presented a true medieval fantasy setting, set on an Earth where legends and folklore were true. It was much more extensive and better defined than other similar settings, such as RuneQuest’s Fantasy Earth (1984-1987), though much of that depth wouldn’t be fully apparent for years.

Third, Ars Magica placed a heavy emphasis on the character’s home–the covenant–and even gave rules for mechanically defining it. This would later be developed into a full book, Covenants (1990). Part of the innovation of Ars Magica‘s covenant system was that it was specifically designed to introduce plot hooks into the game, and thus to build recurring storylines from the start of play.

Fourth, Ars Magica was generally designed with careful attention to mechanics. Jonathan Tweet states that one of the notable innovations of Ars Magica was the target-based skill rolls (or, “die + bonus” as he calls it). Early RPG systems had mostly used simple roll-under mechanics (e.g., percentages) or roll-over mechanics (e.g., THACO). They were ultimately limited in range by a die roll, and initially offered no opportunities for comparison contests (though games like Pendragon were starting to work on the later problem).

Tweet felt the need to have contests, modifiable rolls, and results that weren’t bounded by die size. Thus he introduced “die + bonus” and targets in Ars Magica. The idea was a wave that hit the industry at the time; it can also be found in Talislanta (1987) and Cyberpunk (1988).

However just putting out a solid, innovative game system isn’t enough, and Lion Rampant soon realized this. With boxes of the game now filling Tweet & Rein*Hagen’s home, the crew realized they needed to figure out how to sell the game.

The first sale was eventually made to a local college store on consignment. With the money they earned, the Lion Rampant staff promptly bought a keg of beer. Later on Greg Stafford of Chaosium would get Lion Rampant a list of distributors in the gaming industry, and they’d eventually make their first distributor sale to Wargames West.

Ars Magica‘s first notable success came via a much more unlikely source. Lisa Stevens published a short story called “Night of the Wolf” in Polyhedron Newszine #40, cover dated March 1988. It was about her Ars Magica character, Lupus Mortis, and included game stats for both Ars Magica and Advanced Dungeons & Dragons. This brought Ars Magica to the attention of RPGA members and resulted in it winning the “Gamer’s Choice Award for Best New Role-Playing Game from the RPGA” for 1988. After the presentation of that award at Gencon 1988 numerous gaming distributors picked up Ars Magica, and Lion Rampant was suddenly on its way.

More Publications, More Ideas: 1988-1989

Ars Magica also received some attention at 1988’s other big gaming convention. In the Origins 1988 issue of a small publication called White Wolf Magazine Ars Magica received a stellar review from Stewart Wieck. He mainly praised the magic system, but also offered positive comments on the storytelling elements of the character creation. In that same issue (#11), the first of many articles by Tweet, Rein*Hagen, and Stevens appeared, this one describing the background of the Ars Magica magicians.

Numerous additional articles followed in the next couple of years. More notable were: “The Fate of the Grog” (in #14), which offered suggestions for making the henchmen-like characters of Ars Magica more than just cannon fodder; “The House of Hermes” (in #16), which detailed the many different orders of magicians that magi could belong to in Mythic Europe; and “Troupe Style Role-Playing” (in #21), which offered a totally new way to roleplay.

If troupe style role-playing had ever caught on it would have been the biggest change in roleplaying since Gary Gygax first decided to individualize fantasy characters, way back in the fantasy supplement for Chainmail‘s second edition (1972). Troupe-style roleplaying suggests a style of playing where players change who they play from game-to-game within a campaign, sometimes playing powerful magi and sometimes humble warriors, and it also suggests that multiple gamemasters can take turns running the story, each having control over some part of the world. If Whimsy Cards gave players a little bit of control over their stories, troupe style role-playing knocked the idea out of the park by making everyone equal participants in a game’s saga.

Troupe-style roleplaying also rather deftly introduced a “metagame” to Ars Magica that was larger than any individual play session. By encouraging players to change up their characters it suddenly became OK for characters to have dramatically different power levels, because everyone would get their own time in the limelight. You didn’t have everyone playing magi all the time–which might well break Ars Magica–and likewise no one got stuck always playing a grog.

That 1990 White Wolf article probably remains the best published explanation of troupe style role-playing. The concept was also incorporated into the second edition (1989) of Ars Magica, but not as fully explained. However, in the almost twenty years since, no other major game has ever pushed the idea. The latest, fifth edition (2004) of Ars Magica still gives a couple of pages to the idea, but that’s probably the only place you can find it mentioned.

Besides writing very regular articles for White Wolf Magazine Lion Rampant also published a few more innovative products of their own.

One was their idea for a “jump-start kit”, of which they published two. The first was Bats of Mercille (1988, 1989) and the second was The Stormrider (1989, 1991). Tweet has long desired to offer simpler introductions to roleplaying that gradually eased players into the system. The jump-start kits were his first experiments in this regard, providing lots of handouts which helped players to slowly learn the game. (Tweet has further refined this concept in recent years for the Dungeons & Dragons game.)

Much more notable was The Order of Hermes (1989), which developed the idea of twelve different wizardly organizations that players could join in Ars Magica. The new book gave players real handles to start playing their characters, and story seeds to carry them into the future: the desires of a House of Hermes could be used as plot hooks throughout a campaign.

There had been a few predecessors to this idea of player character organizations. Tweet himself cites Cults of Prax (1979), which provides information on the numerous cults that players could join in RuneQuest. Paranoia (1984) was another early game which offered each player their own organization and thus their own view of the world. However, The Order of Hermes really went the next step by providing more background and material that was more gameable (especially for long-term play, never a strength of Paranoia).

The Order of Hermes has been much copied, first by Rein*Hagen himself, at White Wolf, and later by pretty much the whole industry. Cults of Prax might have been the true origin of the modern splat-books which fill game store shelves today, but The Order of Hermes is the missing link.

In this time period Lion Rampant also played with releasing tapes of mood music for RPGs. The first was called Bard’s Song: Battle Cry.

An innovative product that never quite got released by Lion Rampant was the Ars Magica LARP. Live-Action Roleplaying Games had been slowly gaining momentum in the 1980s, particularly in Europe and Australia. The Ars Magica LARP imagined a wizard’s tribunal–occurring every seven years in the world of Mythic Europe–where wizards came together to engage in politics and diplomacy. Lion Rampant ran a few Ars Magica LARPs, including events at GenCon and Dragon*Con, but no book was ever published. Mark Rein*Hagen would follow-up the idea with Mind’s Eye Theater (1993) for Vampire, while an Ars Magica tribunal LARP would finally see print over a decade later as a book called The Fallen Fane (2004).

A Year of Tribulations: 1989-1990

Despite their originality and innovation, starting in 1989 Lion Rampant began to face both departures and financial problems.

First up, Jonathan Tweet left Lion Rampant in 1989 to go start a “respectable” career. However, he wouldn’t be away from the gaming industry for long. He’d be back freelancing by 1990 and running Wizards of the Coast’s RPG division by 1994. Nonetheless, he was permanently gone from Lion Rampant.

Meanwhile, Lion Rampant’s economic position was growing dire. Despite the acclaim that Ars Magica had received, the company were running up debt and having increasing problems printing new products.

Enter Dan Fox. He was an independently wealthy southerner who literally showed up on Lion Rampant’s doorstep one day. He wanted to publish his own RPG, Hahlmabrea, and he was willing to fund Lion Rampant if they just took care of this little matter for him.

Hahlmabrea is what indie game designer Ron Edwards would later call a fantasy heartbreaker–an RPG that plays like a second-generation Dungeons & Dragons game, without much attention paid to the evolution of game design since the 1970s. Fox’s original name for the game, Warriors, Witches, and Wizards, highlighted the problem. He thought that by having three alliterative subjects in his title he’d set it apart from mere two-topic titles like Dungeons & Dragons and Tunnels & Trolls.

Nonetheless, publishing Hahlmabrea seemed like a good deal for Lion Rampant. Fox would pay off their printers and buy them computers, and all they had to do was publish his game. There was, however, one catch. Fox lived in Georgia, and he had family there, so he wanted to stay. Lion Rampant would have to relocate to the south. But, with Fox offering them a house to live in, the choice wasn’t too hard. In 1990 Lion Rampant pulled up its roots and left for the south.

This was when former President John Nephew left Lion Rampant, along with Woody Eblom, neither of whom wanted to leave Minnesota. John Nephew almost immediately formed Atlas Games, which published five licensed adventure books for Ars Magica from 1990-1991–almost as many as Lion Rampant. Atlas Games will be the subject of a Brief History in the near future.

Meanwhile, down in Georgia, Lion Rampant found out that everything wasn’t as it’d initially appeared. Dan Fox’s wealth wasn’t quite as great as had been implied, and one morning the Lion Rampant crew found the actual owner of their new house stopping by to tell them that they were going to have to move. Mark Rein*Hagen was ready to close up shop, but then a plan was hatched …

(Meanwhile, Hahlmabrea was later self-published by Sutton Hoo Games.)

White Wolf & Lion Rampant: 1990-1991

Lion Rampant had been friends with the folks at White Wolf Magazine for a while. Since that summer 1988 review of Ars Magica Lion Rampant and White Wolf Magazine were quite closely linked. From issue #11 to issue #23, an article about Ars Magica written by Mark Rein*Hagen, Jonathan Tweet, Lisa Stevens, or some combination thereof appeared in almost every issue of the magazine.

White Wolf Magazine had been more economically successful than Lion Rampant, and as a result they had good printer credit. Lion Rampant, meanwhile, had ramped up enough that they could pay for the printing, artwork, and writing of a gamebook out of its autoship, but because of their cashflow issues they didn’t have the credit they needed to get this cycle going again.

So, the companies–by crazy chance now located in adjacent states in the south, White Wolf in Alabama and Lion Rampant in Georgia–decided to merge. Though the Lion Rampant brand was kept for another 9 months while sales of old Lion Rampant supplements paid off old Lion Rampant debts, White Wolf immediately started printing the new books. Stewart Wieck made the announcement of this merger in White Wolf Magazine #24:

Well, about a week after it was first suggested in late September, White Wolf Publishing and Lion Rampant have merged to form a single game company called White Wolf. This new company will continue to offer all of the products available from each in the past.

Being able to print books again was vitally important for Lion Rampant because Mark Rein*Hagen had big ideas. He wanted to write not just a single game, but instead a series of interlinked games which together depicted many different aspects of a single society. His original plan for a second game was called Shining Armor, which would look at knights in the world of Ars Magica–but the success of Pendragon in the field eventually deterred him. Instead he decided to expand the world of Ars Magica into the modern day. As wrote in a 1989 newsletter:

The last idea that’s floating around right now is a game about wizards, very much like Ars Magica, even to the point that there is an Order of Hermes–only set in the present day. Magic has been chased from the earth by the ever-powerful Dominion, but a few creatures of magic and might still manage to hang on in out of the way places. The wizards are part of normal society, covenants may even be corporations, but on certain nights, when the Dominion falls, they can cast their spells with impunity again. But on those nights, others emerge as well…. Since no one takes evil seriously anymore, it has been breeding and growing stronger and stronger. Vampires, werewolves, and even goblins still exist.

Therein he hinted at the basic ideas for three future games: Vampire: The Masquerade, Werewolf: The Apocalypse, and Mage: The Ascension, which would eventually become the cornerstones of the White Wolf Game Studios.

Thanks to conversations on the way to GenCon ’90, by the time of the merger Rein*Hagen was ready to push on one of those new games: Vampire: The Masquerade. But the story of Vampire is part of the story of White Wolf, which will be the subject of the next Brief History.

Latter Days: 1991-Present

What’s perhaps more amazing than Lion Rampant’s tale of innovative production over their three years of operations is the success of its principals since.

Mark Rein*Hagen stayed on with White Wolf, who published his Vampire: The Masquerade roleplaying game in 1991. It quickly overtook Call of Cthulhu as the top horror RPG and catapulted White Wolf into the top tier of RPG companies.

Lisa Stevens quickly moved on to the young Wizards of the Coast, but ended up leaving after the Hasbro buyout to set up her own company, Paizo Publishing, which now licenses the Wizards of the Coast gaming magazines. Ironically for a time she was publishing Polyhedron, the same magazine that her 1988 Ars Magica story was published in, and which helped to get everything going.

Jonathan Tweet further pioneered the storytelling branch of roleplaying with Over the Edge (1992) and Everway (1995). The latter was published by Wizards of the Coast after he joined Lisa Stevens there. He was then selected by Wizards to perform the biggest renovation ever of Dungeons & Dragons (2000). He ended up incorporating a number of ideas from Ars Magica, most notably “die + bonus” rolls and an increased emphasis on spheres of magic.

John Nephew’s Atlas Games continues to publish today. Besides those Ars Magica supplements it also published Tweet’s Over the Edge, and continued pioneering storytelling roleplaying with works by Robin Laws. Today Atlas holds the rights to Ars Magica.

Woody Eblom, who had also stayed in Minnesota, formed Tundra Sales, a “sales and service organization” for small press RPG publishers. It was eventually subsumed into R. Talsorian, then disappeared in 2006.

Nicole Lindroos became a freelancer and also co-founded Adventures Unlimited magazine (1995-1996). It’s perhaps not a surprise that the first issue of that magazine included adventures for Ars Magica, Vampire: The Masquerade, and Over the Edge, all games Lindroos had been involved with. More recently, with husband Chris Pramas, Lindroos formed Green Ronin Publishing, one of today’s star publishers of d20 material.

With so many talented individuals who have had so much continued success in the industry, one can only wonder what might have happened if Lion Rampant could have remained intact.

Thanks to Lisa Stevens for extensive comments and anecdotes, to Nicole Lindroos for additional comments, to Allan Grohe for some corrections and editing, and to John Nephew for looking things over. This article is also partially based upon various online interviews, White Wolf Magazine issues #11-24, and Lion Rampant’s newsletter Running Rampant. It’s further based on my own long-term interest in Ars Magica, which I’ve been playing since 1989 and had the honor to do some writing for from 1992-1993. Tribunals of Hermes: Rome was the first professional RPG work I ever completed (though not the first that was published, given the usual vagaries of publication).