White Wolf today is one of the top companies in the RPG industry, currently claiming a 25% share of the industry. Thus, its rise from very small beginnings is all the more amazing.

This article was originally published as A Brief History of Game #11 & 12 on RPGnet. Its publication preceded the publication of the original Designers & Dragons (2011). A more up to date version of this history can be found in Designers & Dragons: The 90s.

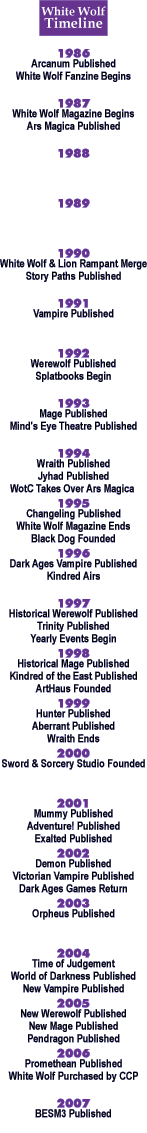

The Origins of White Wolf Magazine: 1986-1990

As described in the histories of Paizo Publishing and Pagan Publishing there’s a tendency for RPG companies to get their start publishing a roleplaying magazine. This was the case with White Wolf, but what’s perhaps more surprising is the magazine that got them their start. It was called Arcanum, and thirty copies of it were published in June of 1986.

Thirty copies is really the smallest of small press, but the response was sufficient for editor-in-chief Stewart Wieck to believe that there was a potential business in his fanzine. However, TSR’s Unearthed Arcana (1985) had too similar of a name so Stewart decided an alternative title was required. He settled upon White Wolf, after the fantasy hero Elric of Melniboné.

The new White Wolf appeared in August of 1986. Like its predecessor it was a stapled and photocopied fanzine, not really the stuff of which a future top-tier RPG company is made. But Stewart (and his brother, Steve) persevered. Over the next couple of issues the print run jumped to 140, then 200. With issue #4 the magazine was professionally printed. With issue #5 a second color was added to the cover, and distributors–beginning with Glenwood Distribution, run by Bob Carty–began to order the magazine, resulting in a print run of 1120.

A big change came with issue #8 cover-dated December 1987. The cover went full-color glossy, the name was changed from White Wolf to White Wolf Magazine and most importantly 10,000 copies were printed. Many were given away at GenCon, getting out the word on the magazine in a big way.

Early issues of White Wolf were primarily about AD&D, but with issue #8 that changed too, and the magazine became more “indie”. Over the next 16 issues, White Wolf would publish numerous articles about SkyRealms of Jorune (#8-16), Ars Magica (#11-24), and RuneQuest (#15-22), most by the authors of those games. As White Wolf increasingly pushed indie games it eclipsed Different Worlds (1979-1987) the former star in the category (which was just then ending its run).

In the December 1990 issue of White Wolf Magazine White Wolf had a surprise announcement: they were merging with Lion Rampant, the aforementioned publisher of Ars Magica. White Wolf’s Stewart Wieck and Lion Rampant’s Mark Rein*Hagen were to be the co-owners of a new company, the White Wolf Game Studio.

(See the Brief History of Lion Rampant for some of the reasons behind this merger.)

Enter Story Paths: 1990

White Wolf had already published some books of their own including a small-run Stewart Wieck adventure called The Curse Undying (1986) and a book of settings called The Campaign Book Volume One: Fantasy (1990), but the first product that really combined the resources of Lion Rampant and White Wolf was an unassuming gaming accessory called Story Path cards, which expanded on Lion Rampant’s Whimsy Cards.

The Whimsy Cards had been an innovative pack of 43 cards which gave players the ability to slightly control the storyline of an RPG by playing cards with text like “bad tidings”, then explaining how that card influenced the plot of the game. White Wolf released two decks of “Storypath” cards: The Path of Horror (1990) and The Path of Intrigue (1990). There were originally supposed to be six more of these 24-card decks–including Danger, Hope, Deception, Discovery, Whimsy, and Suspense–but they were never produced.

The Story Path line ended abruptly when they were traded to Dan Fox, who had previously invested in Lion Rampant. He’d later sell them to Three Guys Gaming, who released a new edition of 81 cards in 1996 then dropped off the face of the earth.

For White Wolf, there were much bigger things to come.

Enter the World of Darkness: 1991

Over at Lion Rampant, Mark Rein*Hagen was constantly juggling numerous ideas. His Ars Magica game had been successful at creating the definitive games of magicians, and now he wanted to do more.

His first idea was to create a series of linked games set in the middle ages, beginning with a knightly game called Shining Armor. Then he considered moving Ars Magica into the modern day as an urban fantasy. Inferno was another early idea; it would have been a game where players roleplayed in Purgatory, perhaps even taking on the roles of characters who had died in other campaigns. (A transformer explosion and the unlikely destruction of the sole manuscript led the team to decide that particular game was cursed.)

On the road to GenCon ’90 with Stewart Wieck and Lisa Stevens, Mark Rein*Hagen hit upon a game that combined all of these concepts. It would be more dark and moody like Inferno, it would be an urban fantasy that inherited some history from Ars Magica, and it would be the first in a series of linked games.

He called the game Vampire: The Masquerade and it was Rein*Hagen’s main project over the next year.

In early 1991 Vampire was reaching completion, and White Wolf pulled out all stops in a new marketing drive. They prepared a 16-page full-color glossy pamphlet which described their new game and sent thirty or forty thousand copies to distributors to give away. This got players, retailers, and distributors alike excited about the game, priming the industry for their new release.

The pamphlet nailed the intentions behind the game, as the following prose quote displays:

She passes me by with a quick glance into the alley. I break away from the shadows. An arm’s-length away, I can hear her heart pumping.

I have become death, the destroyer of souls.

Gliding toward her, the smell of her life-plasm waifs over me, arousing me. She is only inches from my caressing touch. My mind screams with lust.

NO!

White Wolf was trying to evoke a very specific mood with their new game: a gothic feel that really hadn’t been seen in role-playing games before, except in TSR’s classic Ravenloft (1983).

This gothic mood began with the game’s dramatic cover, which featured a single red rose and an ankh laid on green marble. It was a photograph that White Wolf took after their first cover, by Dan Frazier, came in looking too much like every other roleplaying game. The spontaneous photograph of that green marble instead produced a wonderful, unique, and iconic vision of the game.

However, it wasn’t just the cover of Vampire that was startling. The entire game was different from anything seen before in the roleplaying community. In the best tradition of Anne Rice’s Interview with a Vampire, White Wolf’s new game revealed a world of politics, machinations, angst, and internal conflict. Though RPG games were already becoming more about plots and people–and less about dungeons and fighting–centering a whole game on these subjects was entirely new.

Rein*Hagen’s former mechanics guy, Jonathan Tweet, had by then (temporarily) left the industry so Rein*Hagen turned to a new designer for his new game: Tom Dowd, the co-designer of Shadowrun (1989). As a result of Dowd’s history, some Shadowrun mechanics inevitably seeped into Vampire, most notably “comparative” dice pools. This was a new method to roll dice that Shadowrun had innovated. Skill values determined the number of dice to roll, but the dice weren’t added up (as in Champions, Tunnels & Trolls and other early games which featured “additive” dice pools). Instead each individual dice was compared to a target number, then the total number of successes was counted.

Dowd adapted the Shadowrun mechanic fairly exactly for Vampire, though the type of die changed (from a 6-sider to a 10-sider). The system offered both good and bad to the new RPG. On the downside, the probabilities of the system are confusing. It’s a rare player who can quickly say what the odds are of “rolling 3 successes on 7 dice requiring a 7+ for success”. However, this deficit for more serious gameplayers was offset by a benefit for more casual and first-time players: skill levels were low and so could be represented by filled-in dots on character sheets, making the game look much less intimidating than the number-heavy standard for RPGs.

Two other game design elements were notable in Vampire‘s success: disciplines and clans.

Disciplines–such as dominate and other vampiric powers–effectively made Vampire a dark super-hero game rather than a horror game. Horror games had always been a hard sell, with Call of Cthulhu a very rare standout. Conversely, superheroes were a proven winner in roleplaying.

Clans–which were the specific organizations that vampires were part of–made the game more accessible. Though Rein*Hagen’s last game, Ars Magica had featured the similar Houses of Hermes, it was actually Chris McDonough who suggested clans for Vampire. It was late in the game design process, and playtesters were having troubles with character concepts. McDonough suggested that something like D&D’s character classes was needed. The result was the Vampire clans, which depicted standard vampiric archetypes; they would be invaluable as Vampire reached out into new communities of players with its gothic styling.

White Wolf’s marketing blitz was successful, and the game was sent back to the printers within a week of its initial release.

Five Years, Five Games (Plus One): 1991-1995

Following the ground-breaking release of Vampire: The Masquerade, White Wolf did something every bit as innovative and amazing: they put out a new roleplaying game–each set in Vampire‘s World of Darkness and each using Vampire‘s Storyteller rule system–every year. The next four games were: Werewolf: The Apocalypse (1992), Mage: The Ascension (1993), Wraith: The Oblivion (1994), and Changeling: The Dreaming (1995).

Each new core book featured an abstract, iconic cover. Some were attractive, but none as impressive as Vampire‘s green marble. There were also some missteps. Werewolf featured die-cut claw marks on its original cover which easily ripped. Wraith was called “noseroids” by some wags due to the game’s nearly unreadable cover logo.

Inside the covers, each game built upon the core strengths of Vampire. They featured dark, dystopic visions of the world. They centered on super-powered peoples. They included character organizations to give players character concepts. Though each of these new lines inevitably harkened back to Vampire, they also were each unique.

Werewolf, with its magical protectors of Gaia, looked at the World of Darkness in a very different way, thus showing how one setting could support two very different viewpoints.

Mage was, to a certain extent, a game that Rein*Hagen had imagined way back in 1989 when he first talked about the possibility of a modern-day Ars Magica though now the Order of Hermes appeared as a single tradition among many. It was also the first World of Darkness game which Rein*Hagen was not explicitly involved with.

Wraith is often lauded as the most consistent and moody of the original White Wolf games. It also featured a roleplaying innovation, the “Shadow Guide”, where each player acts as another character’s evil side, trying to tempt and cajole him to the way of darkness. This returned to ideas of “troupe” roleplaying which Rein*Hagen had introduced at Lion Rampant.

Changeling was bright and beautiful, a real contrast to the other World of Darkness games. It was also one of the earlier full-color gamebooks. Changeling‘s original magic system, however, was controversial. It used “Cantrip Cards” which were sold in CCG-like collectible packs.

One of the problems with White Wolf’s rapid expansion of game lines was that the first editions of the games were often flawed, to the considerable disgruntlement of fans. As a result additional editions were often quickly released. Between 1992 and 2000 the more successful lines of Vampire, Werewolf, and Mage received three editions each, while Wraith and Changeling each received two. Some games changed more than others. Mage, for example, included considerable thematic changes as each edition was released.

Another problem, as we’ll see, is that not all game lines were equally successful. From Wraith onward, White Wolf would see diminishing returns.

Besides their five RPGs, White Wolf also expanded the World of Darkness in another direction–live action roleplaying games–starting with Mind’s Eye Theatre: The Masquerade (1993). Rein*Hagen had been thinking about LARPs since Ars Magica, but this was the first time his ideas saw print.

The original iterations of Mind’s Eye Theatre were somewhat rough. This was often the case with Rein*Hagen designs: he has a unique, creative touch for design, but not an editor’s soul. As a result additional designers were brought in to help polish the game. One of these was Mike Tinney, who had been running LARPs of his own in the northeast. Tinney would become the Mind’s Eye Theatre line manager and would later rise up much higher within White Wolf.

Although not as much of a commercial success as the tabletop RPGs, the Mind’s Eye games remain influential. They are perhaps the only commercially successful LARP line, and they’ve likely brought numerous new people into the hobby, among them many women.

Five Years, Many Supplements: 1991-1995

Beyond the rule books, White Wolf also supported each of these new games with a full game line, meaning that by 1995 they were juggling five different World of Darkness games.

The support of so many game lines meant that a huge mob of people actually helped the World of Darkness to grow and evolve. Andrew Greenberg, the original Vampire line editor, and Bill Bridges, the original Werewolf line editor, were two of the most notable because they helped to define the look and feel of the entire World of Darkness. However, there were many more.

Each game line was clearly marked, using those iconic backgrounds from the core game books. You could recognize a Vampire book by its marbled background and a Wraith book by its black and white chains. This is a general marketing methodology that White Wolf has carried across all of its lines, from Ars Magica‘s tome covers to Exalted anime stylings. Product line branding is more common in the industry today but it was more notable in 1991.

There were campaign books and adventures among the early supplements, as you’d expect, but White Wolf also popularized a new sort of supplement: the splatbook. Splatbooks detail a specific race, class, or organization for a roleplaying game. They’re generally player’s books, and thus sell to the entire player base–which is usually much more profitable than selling to just gamemasters, as traditional adventures do.

Splatbooks had actually been around since almost the dawn of roleplaying. Chaosium’s Cults of Prax (1979) was an early release and GDW quietly built much of their classic Traveller line around splatbooks, from Mercenary (1978) to Darrians (1987). Even Lion Rampant had put out a splat book, The Order of Hermes (1990).

However no one had ever put out splatbooks as consistently and in such volume as White Wolf did. Clanbook: Brujah (1992) was the first. It focused on a single vampiric clan, leaving room for another dozen splatbooks in the same line. White Wolf would go on to produce splatbooks for all of their initial lines except Wraith, and the term “splatbook” was eventually coined for White Wolf’s releases. However, though White Wolf generally gets the credit for this innovation, it was really an industry trend. TSR introduced similar products around the same time, beginning with The Complete Fighter’s Handbook (1989).

Two other innovations appeared in White Wolf’s early supplements: metaplot and crossovers.

Metaplots have been around since Traveller started publishing its Traveller News Service in The Journal of the Travellers’ Aid Society #2 (1979). The concept was simple: a gameworld slowly changed through a game’s publications. The benefits of metaplot are that they can keep a setting dynamic and they can introduce real drama. The deficits are that they can railroad players and can write them out of the most dramatic changes in a setting. Their use is sometimes controversial.

The first World of Darkness rulebooks had briefly touched upon metaplot. Vampire mentioned an Armageddon-like “Gehenna” while Werewolf played up the idea of the “Apocalypse”, even including it as part of the game’s title. However it was in the supplements that these plots really began to grow–though slowly at first. For example the setting described in Chicago by Night (1991) was changed when Prince Lodin was killed in Under a Blood Red Moon (1993), which was reflected in the second edition of Chicago by Night (1993). The idea of metaplot would mature and largely take over the production of the World of Darkness games in the later 1990s and early 2000s.

Crossovers were a bit more innovative within the game industry, mainly because not too many company had settings that could be crossed over. TSR’s Spelljammer (1989) had been one of the first, but White Wolf, with all of their lines set on the same world at the same time, would go after the idea much more aggressively.

Under a Blood Red Moon (1993) was one of the earliest crossovers, putting both vampires and werewolves into the same story. Unfortunately Under a Blood Red Moon would suffer from the same flaw as all later White Wolf crossovers that tried to put multiple supernatural entities into the same adventure: though five game lines had been intended from the start, they were each somewhat different, and the rules never meshed entirely well.

White Wolf would begin pushing crossovers much harder in 1995, with “The Year of the Hunter”. Expanding upon the idea of Vampire‘s The Hunters Hunted (1992), White Wolf produced five sourcebooks, one for each of their games. Each detailed the background for a group hunting the game’s title characters. It was a clever way to encourage collectors to look at all of White Wolf’s lines and to encourage cross-fertilization from one game to another. It also avoided the problems of true crossovers, like Under a Blood Red Moon, because it was a theme crossing the game lines, rather than actual characters.

Many more yearly crossovers would follow, beginning in 1997. Some would be thematic like this one–presenting similar books for different lines–but many others would instead be largely plot-driven.

Licensing the World of Darkness: 1994-1995

As White Wolf approached their original five-game goal, two other notable World of Darkness products appeared, both licenses.

The first license was the inevitable CCG. After their 1993 release of Magic: The Gathering, Wizards of the Coast started gobbling up licenses to produce RPG-based CCGs. Vampire: The Masquerade was one of the few such licenses that they put to use.

The Vampire CCG was original called Jyhad (1994), but this name was very soon changed to Vampire: The Eternal Struggle due to concerns of offending Muslims. It was designed by Richard Garfield, the designer of Magic, and was an innovative CCG design that worked very well for multiple players–not just two. Vampire: The Eternal Struggle was published by Wizards of the Coast from 1994-1996.

It worth briefly noting that there would be a few other World of Darkness CCGs. White Wolf produced one Werewolf-based CCG called Rage (1995-1996) and Five Rings Publishing produced another (1998-1999). In addition White Wolf would later publish Vampire: The Eternal Struggle (2000-Present) on their own. However these CCGs lie largely outside this history of RPGs.

The second license had the potential to be even bigger than a CCG. White Wolf sold the rights to produce a World of Darkness television show to Aaron Spelling, the man behind Beverly Hills 90210. Kindred: The Embraced didn’t make the fall 1995 schedule, but it would eventually run from April 2 to May 8, 1996. Like Spelling’s other works, it mixed drama and soap opera.

The show was cancelled after just eight episodes. Many folks thought it was quite bad, but nonetheless it was quite a laurel for the industry. The Dungeons & Dragons (1983-1985) cartoon had marked roleplaying’s one previous foray into television; Kindred was its first prime-time outing.

The interest that both Wizards of the Coast and Aaron Spelling showed in Vampire highlights White Wolf’s position as a prime producer of intellectual property. In fact, more than that, they’d become a top-tier RPG company. TSR was then still #1, but in the few years since they’d exploded onto the scene White Wolf had gained considerable market share.

Only Palladium and FASA were really competing with them in sales, and White Wolf consistently put out more new top sellers. After a quick and meteoric rise, by 1995 White Wolf was the #2 publisher of RPGs in the industry.

The Merger Remnants: 1991-1995

Of course before there was ever a World of Darkness, Lion Rampant and White Wolf each had their own businesses: the Ars Magica RPG and White Wolf Magazine. As the World of Darkness evolved, these lines changed as well–and would each eventually disappear, neither being able to survive the comparison to White Wolf’s star sellers.

With the release of Vampire, Ars Magica became a predecessor to the World of Darkness. The political Tremere of Ars Magica had become a vampiric clan, while Ars Magica‘s Order of Hermes was one of many groups of magi in the modern day. In turn the Ars Magica setting became darker–to the distaste of many fans.

White Wolf’s biggest expansion to Ars Magica was a third edition of the rules (1992), generally polishing the rulebook. Like Vampire it was publicized with a color booklet made available to stores.

Beyond that White Wolf put out over twenty Ars Magica supplement from 1991-1994, some of them in series, much like their World of Darkness splatbooks. These included two “Tribunal” books–each of which detailed a portion of Mythic Europe –and three books describing the divine, infernal, and faerie realms of power. Both of these themed series continue to this day, highlighting White Wolf’s successful methods for defining interesting supplements.

By early 1994 Ars Magica wasn’t measuring up to White Wolf’s three successful World of Darkness games. Also by this time Lisa Stevens, Lion Rampant and White Wolf founder, had moved over to another young gaming company, Wizards of the Coast. She offered to have Wizards pick up Ars Magica, and White Wolf agreed. Despite the shared history of the games, Ars Magica and The World of Darkness were now forever separated.

White Wolf Magazine was the other notable property arising from the White Wolf/Lion Rampant merger. Tasked with Stewart Wieck’s original promise to “remain independent” it faced an ever-increasing problem as White Wolf published more games.

In 1992, with issue #31, White Wolf Magazine underwent a graphical redesign. Afterward it paid more attention to White Wolf’s own games. It was by no means a house organ, but it always featured at least one White Wolf article thereafter.

In September of 1993 Stewart Wieck stepped down as President of White Wolf. He’d return to more creative pursuits, helping to edit the various White Wolf lines–to their benefits. He would also establish a new fiction line. To allow for this new creative work Stewart handed over the company reins to his brother, Steve. At the same time he named Ken Cliffe the new editor-in-chief of White Wolf Magazine. Under Cliffe the magazine went monthly starting with issue #39 (January 1994). Cliffe further began to envision a new, more “cutting edge” magazine.

In issue #50 (1995) White Wolf made a final metamorphopsis, changing its name to White Wolf: Inphobia. The magazine was far, far from its origins. It was now mostly full color, and most of the feature articles were about White Wolf games. (The magazines had abandoned its “independent roleplaying coverage” slogan with #47.) There was also an active attempt to expand the magazine into other media, including comics, music, books, and TV.

However none of the changes were enough keep Inphobia going. It was cancelled in 1995 with issue #59.

Between the transfer of Ars Magica and the death of White Wolf Magazine, White Wolf had come to a crossroads. The company was increasingly centered around a single product line, the World of Darkness. Worse, that line was no longer maintaining its upward momentum, between lower sales on later lines and the end of the original five-game vision. New directions were needed.

And that is where we’ll pause, at the end of 1995. We’ve seen White Wolf’s quick rise, and how by 1995 they’d put aside all of their pre-merger lines. Next time we’ll see ups and downs, as White Wolf struggles through CCGs, book market crashes, and the emergence of d20.

White Wolf Fiction: 1993-1998

Under Stewart Wieck White Wolf’s fiction line kicked off with Drums Around the Fire (1993), a collection of Werewolf short stories that was entirely typical for the RPG fiction genre. Authors associated with the game line wrote gaming fiction for a gaming audience (though a few name authors did show up in these early works).

The Book of Nod (1994) got some attention as a high-quality piece of writing that existed inside the game world. However, Dark Destiny (1994) was White Wolf’s break-out fiction book. It was edited by Edward E. Kramer, a professional from outside the industry, and it featured World of Darkness stories by Robert Bloch, Nancy Collins, Harlan Ellison, and many other professionals. They didn’t slavishly devote themselves to White Wolf’s continuity, and thus they presented totally original and innovative views of the World.

Dark Destiny got White Wolf’s fiction noted by book critics–who typically had ignored game-related fiction. Some White Wolf stories would thereafter get “Honorable Mentions” in Year’s Best anthologies. Dark Destiny would also help White Wolf to attract a higher caliber of fiction authors, because it gave them a reputation for giving their writers a bit more creative freedom.

Beyond the World of Darkness White Wolf also began a “Borealis Legends” imprint in 1994. The Wiecks had long loved classic science fiction and fantasy. The Borealis Legends line, which reprinted science-fiction and fantasy classics, allowed them to give something back to the SF community.

Borealis’ most notable publications were: a 15-volume set of books reprinting all of Michael Moorcock’s Eternal Champion novels (1994-1999); a 4-volume series reprinting all of Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and Gray Mouser stories (1995-1998); and an abortive 4-volume series originally intended to reprint 40 Harlan Ellison books (1996-1997). White Wolf also printed original stories in these settings, including the Eternal Champion collections Tales of the White Wolf (1994) and Pawn of Chaos: Tales of the Eternal Champion (1996) and the Fafhrd and Gray Mouser novel Swords Against the Shadowland (1998).

Unfortunately White Wolf’s fiction lines got started at a very bad time. In 1995-1996 book chains like Borders and Barnes & Noble were shutting down mall stores to open up “super” stores. All books sold to book stores are returnable, meaning that the stores can send any unsold books back to the publisher for credit. As mall stores closed, record numbers of returns were sent back to publishers, while new purchases for super stores accounted for just a fraction of those numbers.

This caused financial problems for White Wolf and was the main reason behind painful layoffs in 1995 and 1996. It would also ultimately be a major factor in the failure of Borealis, which tailed off in 1998-1999.

Afterward World of Darkness novels and collections were the main focus of White Wolf fiction. Many later novels would either tie directly to sourcebooks or else would help to push along the metaplot. In the last few years White Wolf fiction has largely ended, with just a single publication in 2006.

New RPGs: 1994-1998

White Wolf was also looking at ways to expand their RPGs beyond the modern World of Darkness. From 1994-1997 they’d publish three new RPGs, create a new game imprint, and reveal the plan for a new sequence of World of Darkness games.

The first new RPG was Streetfighter (1994), based on the video game and using a variant of the Storyteller game system. Although it received some support and marketing through White Wolf Magazine, it was never a notable hit.

Hol (1995) was the second new RPG. It was a new edition of Dirt Merchant’s 1994 RPG. Hol was funny and profane, even offensive. It went against most of the tropes of RPGs. Even if it was never played that extensively, it was innovative and prefigured that wacky directions that indie RPGs would take in the 2000s.

However, Hol also presented a problem. It was sufficiently adult that it might damage White Wolf’s reputation as a publisher of entertainment intended for young adults. Thus it was published under a new imprint, the Black Dog Game Factory, named after a corporation in the World of Darkness.

White Wolf would later use the imprint to publish adult supplements for their own core games. Notables include The Charnel House of Europe: The Shoah (1997)–which adapted the Holocaust for Wraith–and the four-volume Giovanni Chronicles–which traced a family from the 1400s to the modern day (1995-1999). Both of these were quite well-received. Charnel Houses remains a top-100 product in the RPGnet Gaming Index, while the Giovanni Chronicles were award-winning.

White Wolf’s third new RPG of the era should have been the science-fiction game Exile (originally Parsec), which was announced in 1996 and intended for publication in 1997. This Mark Rein*Hagen design used a brand new rule system and was set in a brand new universe–the Null Cosm. It would have been the first of a new series of games, just like Vampire had been. It was described as “a moody, cultured, stylish space opera, rife with mystery and adventure” Rein*Hagen again showed his interest in metaplot by saying, “Null Cosm is a setting and game line designed as a saga, a complete story that will transpire over a number of years.”

However during the financial hardships of late 1996 there was a falling out between Mark Rein*Hagen and the Wiecks. Rein*Hagen decided to leave White Wolf and he took Exile with him. His Null Foundation put out a playtest draft in 1997, but after that the game disappeared off the face of the earth though Rein*Hagen would later produce a collectible action-figure game called Z-G (2001) which also used the Null Cosm background. (One of the action-figure game’s most notable elements was that figures’ poses had game effects.)

Andrew Bates, the former developer of Exile, was thus tasked with coming up with a new science-fiction game, with a publication date just ten months out. Brainstorming with other White Wolfers he came up with a shared universe which included three different time periods, each of which highlighted a different genre: science-fiction, superhero, and pulp. The superhero game would be based upon a pitch already being polished up by Rob Hatch, but everything else was brand new.

Nonetheless the SF game, ÆON (1997), hits its publication deadline. It used a variant of the Storyteller game system and was intended to appeal to a totally different, more action-oriented audience than the World of Darkness.

ÆON has some troubles from the start, due to a lawsuit from Viacom who felt that it violated the trademark of their TV show, Aeon Flux. The names on the original release actually had to be stickered over with the game’s new name, Trinity. Afterward the next two games in the series followed like clockwork: the near-future, superheoric game Aberrant (1999) and the pulp game Adventure! (2001). As was the case with many of White Wolf’s new expansions in this period, they were well-received but not dramatically successful.

Meanwhile White Wolf was planning a new sequence of five World of Darkness games. These would be historical games related to their existing titles. The first three were: Vampire: The Dark Ages (1996), Werewolf: The Wild West (1997), and Mage: The Sorcerers Crusade (1998). Although five historical game lines were originally intended the historical Mage was the last.

One other game was of note in this period, Fading Suns (1996), was not actually published by White Wolf but rather new studio Holistic Designs. It was a science-fiction game created by original Vampire developer Andrew Greenberg and original Werewolf developer Bill Bridges. Many players felt like it had the “White Wolf feel”, no doubt due to the artistic and creative influence that Greenberg and Bridges had on White Wolf’s genesis. Holistic Designs will be the focus of a future Brief History.

Downturn and Arthaus: 1998-2001

By 1998 White Wolf was increasingly in need of a housecleaning. Of their last five World of Darkness game lines only Vampire: The Dark Ages sold well. Worse the book trade problems of 1995-1996 had flowed right into the CCG bust of 1996-1997. Finally Mark Rein*Hagen, one of the founders of the company, was now gone.

On September 14, 1998, White Wolf announced that they were restructuring their business.

This restructuring included changes for all of White Wolf’s less successful lines. Most notably, Wraith: The Oblivion was killed outright despite its critical acclaim, though there would be a few final releases in 1999. However, for Changeling: The Dreaming, Werewolf: The Wild West, and Mage: The Sorcerer’s Crusade White Wolf had a more innovative solution.

It had been the comparatives that were eating at these other lines (just as they had Ars Magica). Changeling, for example, sold well and was enjoyed by many players. It probably would have done fine at a smaller company. However because White Wolf had the overhead of a larger company they couldn’t afford to publish a less successful line … unless they changed the very basic costs of productions.

Which they did.

Based on a proposal by Mike Tinney, now Vice President of Licensing and Marketing, White Wolf created a new imprint called “ArtHaus”. In doing so they moved enough of the creation of the supplements for these lines out-of-house that they could afford to publish them. A recent catalogue describes ArtHaus thus:

What is Arthaus? It’s White Wolf’s newest imprint. White Wolf’s mission has always been to create art that entertains; White Wolf Arthaus is the embodiment of that ideal. Modeled after small press, the Arthaus team strives to create games and projects that are new, experimental and unique. White Wolf Arthaus now manages whole game lines, supports others and creates specialty projects whenever possible, all in keeping with White Wolf’s regular games and books.

White Wolf proved unable to continue Werewolf: The Wild West even under ArtHaus, but Changeling and Mage: The Sorcerer’s Crusade would continue. In addition, Trinity was added to ArtHaus in 2000 and Aberrant in 2001. At the time ArtHaus seemed to be the back lot for White Wolf’s second-tier games, but in 2001 that would change dramatically.

Years of Years: 1997-2003

Meanwhile, the World of Darkness was slowly evolving with new yearly events and many new game lines.

In 1997 White Wolf created another “Year of” event using the same model as 1995’s Year of the Hunter. That was the “Year of the Ally” which offered new companions for the protagonists of all of White Wolf’s current games–then the core five RPGs, plus Vampire: The Dark Ages and Mind’s Eye Theatre.

However by 1998 White Wolf was increasingly looking toward metaplot as a sales tool. Much of this metaplot was embedded in later “Year” events, which continued to crossover the lines, continued to advance the global stories of the World of Darkness, and increasingly were used as the launching boards for new games and sourcebooks.

In the next years, White Wolf published the Year of the Lotus (1998), the Year of Reckoning (1999), the Year of Revelations (2000), the Year of the Scarab (2001), and the Year of the Damned (2002). Two major new lines were launched as part of these events: Hunter: The Reckoning (1999), a game for playing humans in the World of Darkness; and Demon: The Fallen (2002), a game about the newly arrived fallen angels.

In this same period metaplot would take even more center stage with the release of Ends of the Empire (1999), which was not only the last Wraith book, but also a dramatic finale to the line. It allowed player characters to play out the last story in Wraith, ultimately resolving the game’s metaplot–an entirely unprecedented event.

White Wolf’s last hoorah for the original World of Darkness would be their eighth core line, Orpheus (2003)– which featured no subtitle. This was a new look at ghosts, set after the Wraith finale. It offered another unique twist on roleplaying line releases: it was intended as a limited run, with just six books planned from the start. Further, Orpheus was all metaplot, with those six releases telling a story with a coherent beginning, middle, and end.

With their last few core games–Hunter, Demon, and Orpheus–White Wolf was starting to get some of its mojo back. They’re generally well-rated and have each gotten some critical acclaim, particularly Orpheus. However in other ways the World of Darkness was becoming more and more constrained, with the metaplot increasingly driving everything.

The Minor Lines: 1998-2004

With just three core game lines published in the six years from 1998-2003, White Wolf was slowing a bit from their original, somewhat crazy, rate of production. However to fill the gaps between major releases they developed a new method for releasing minor game lines. Instead of putting out a full gamebook (and a game line to go with it) they began publishing minor game lines as sourcebooks which depended upon owning some other World of Darkness book for the rules.

This was the model used for Kindred of the East (1998), and Mummy: The Resurrection (2001), which each spun out of yearly events White Wolf’s fourth historical game, Wraith: The Great War (1999), which was also one of the last Wraith releases, also followed this model

White Wolf never put out a historical game for Changeling, which had already been confined to the ArtHaus line. The Internet rumor mill suggests that it would have been set in the 1960s if it had ever been published. However, White Wolf did later go back to the historical well for their most successful lines. Victorian Age Vampire (2002) was another minor-line sourcebook release.

That same year White Wolf kicked off a whole new product line set in the Dark Ages. It began with a new Dark Ages: Vampire (2002) but was soon followed by Dark Ages: Mage (2002), Dark Ages: Inquisitor (2002), Dark Ages: Werewolf (2003), and Dark Ages: Fae (2004). Following their new methodology each additional game required Dark Ages: Vampire for play. It was a somewhat ironic new product line given White Wolf earlier abandonment of Ars Magica, set in the exact same time period.

Beyond the World of Darkness: 2000-2006

Meanwhile White Wolf was back to the same problem that they’d faced in the 1990s. They didn’t want all of their eggs in the World of Darkness basket. They needed something more–and as it happens something more was just then hitting the industry: the d20 license. Their new expansion into this arena would be much more successful than their attempts in the 1990s.

A September 13, 2000 press release announced White Wolf’s expansion into d20:

Sword & Sorcery Studio and Necromancer Games have allied with White Wolf Publishing, Inc. to distribute the new studios’ products to hobby game stores and book stores world-wide. White Wolf Publishing, Inc. is the sales and administration division best known for marketing White Wolf Game Studio’s World of Darkness product lines such as Vampire: the Masquerade.

The press release painted Sword & Sorcery Studio as a separate publishing house which White Wolf happened to be distributing. However the truth behind Sword & Sorcery Studio was much more complex. Sword & Sorcery itself was a division of White Wolf where White Wolf staff worked on d20 products including their lead release the Creature Collection and the related Scarred Lands product line. Meanwhile Necromancer Games was providing d20 legal experience and know-how, as well as publishing their own products under the imprint name.

Several other studios would later join Sword & Sorcery, most notably Malhavoc Press, run by Monte Cook–one of the designers of the third edition Dungeons & Dragons/d20 system. Guardians of Order’s A Game of Thrones (2005) would also be published under Sword & Sorcery. The imprint would further publish some ArtHaus products including: White Wolf’s new d20 versions of Ravenloft and Gamma World; paper RPG versions of the MMORPGs EverQuest and Worlds of Warcraft; and d20 versions of the Trinity line.

Designing d20 games for Sword & Sorcery allowed Arthaus to become more than just the backline World of Darkness publisher. They soon began publishing totally new game lines as well.

Pendragon was published in a new fifth edition (2005) by ArtHaus, then followed up by The Great Pendragon Campaign (2006), possibly the most wide-reaching RPG metaplot ever, with its outline for an 80-year campaign.

ArtHaus also acquired some of the assets of Guardians of Order during the latter company’s 2006 bankruptcy. They’ve since published a new third edition of the anime game Big Eyes Small Mouth (2007) and also hold rights to Silver Age Sentinels and Hong Kong Action Theater.

Separate from ArtHaus or Sword & Sorcery, White Wolf launched one more fantasy line in this time period: Exalted (2001). Like the rest of its core games, Exalted is based on the Storyteller System. The background is super-heroic fantasy, much in the same line as White Wolf’s super-heroic horror, and following the trends of third edition Dungeons & Dragons. Originally Exalted maintained some tenuous ties to the World of Darkness, acting as a sort of pre-history with a few names used in common (like Ars Magica, but to a far lesser degree). However, given the more recent changes to the World of Darkness, which we’ll see shortly, that’s since been largely dropped.

As was the case with Vampire, White Wolf had a cover in-house for Exalted, but then they decided it didn’t have the look they wanted. Instead White Wolf developed a new anime-influenced cover–a style which has since been adopted for the entire line, and which helps the line to dramatically stand out amidst the huge mass of fantasy games on the market.

Exalted has done quite well. Some place it at a similar success level as latter-day Vampire products. A full-color second edition of the game was released in 2005.

Presidencies & Legalities: 2002-2005

In 2002 Steve Wieck, who had been President of White Wolf for nine years, relinquished that role. Mike Tinney was named the new President. He’d oversee notable changes at White Wolf, including a massive renovation of the World of Darkness.

Under Tinney’s watch, White Wolf also became involved in two notable legal actions.

First was a dispute with White Wolf’s fanclub, the Camarilla. Starting in 1998 the Camarilla had become increasingly aggressive about acting as an independent business. They trademarked their name in 1998 for use as a fan club–despite the fact that the term was already trademarked by White Wolf–and in later contract negotiations asked for increasing concessions from White Wolf. In 2003 White Wolf attempted to take over the Camarilla, and the board members of the Camarilla filed a lawsuit against White Wolf in a Utah court. White Wolf counter-sued and won. The Camarilla filed for bankruptcy on February 15, 2003. White Wolf was thus able to take over the club.

On September 5, 2003 White Wolf sued Sony Pictures and a few other studios for copyright infringement over a movie named Underworld. It told a Romeo & Juliet like story of werewolves and vampires. White Wolf alleged that it infringed on a short story they’d published by Nancy Collins called “Love of Monsters”. This suit was eventually settled out of court.

Old and New Worlds: 2003-2006

Under new President Tinney, the focus of White Wolf soon shifted to a total revamp of the World of Darkness. In many ways the line had been floundering for years. The decision to release a game a year–which had looked so good back in 1991–had mostly failed after Mage. Likewise the metaplot was increasingly a point of contention among players, and in all likelihood was one of the reasons behind the lines’ slow decline. As with serial TV shows many consumers felt like they couldn’t keep up and were forced to drop White Wolf products as a result.

White Wolf decided that a big change was needed, and in 2003 they announced the Time of Judgement–the final major event for the original World of Darkness. Just as they’d done for Wraith a few years before, White Wolf announced that they were going to publish a series of adventures that brought all of their metaplots to a conclusion, thus ending all of their modern World of Darkness game lines.

Response to the announcements about the Time of Judgement was entirely incredulous. Some companies had staged major events to bridge editions, such as the Avatar series (1989) for the Forgotten Realms. However no one had ever totally destroyed their setting and closed down their game lines, as was being done here. The closest analogy was GDW’s bridge from Megatraveller to Traveller: The New Era (1993) and given the quick failure of the latter line–partially because players were infuriated with the scrapping of their setting and game system–it wasn’t a good model.

Nonetheless the Time of Judgement books sold very well–largely on par with older books before the lines had declined.

A new World of Darkness was, of course, the obvious next step. It featured what the comic world calls a “reboot”. Many old elements appear in the new World of Darkness, but not necessarily put together in the same manner, and the continuity between the two worlds is explicitly quite different.

As part of the new World of Darkness a new game system appeared, the “Storytelling” system, as opposed to the older “Storyteller” system. It’s largely the same, with some simplification. More importantly the rules for the entire world are now gathered in a single rulebook called The World of Darkness (2004).

Each core game setting now has a sourcebook, containing only the specific rules for those peoples. The core settings are the original three World of Darkness lines from 1991-1993, now called: Vampire: The Requiem (2004), Werewolf: The Forsaken (2005), and Mage: The Awakening (2005). The new World of Darkness coheres much better than the original, solving the old problem of crossing over supernatural creatures from one game to another.

White Wolf continues with their plan to release a game a year, but they’ve decided to follow the Orpheus model. Each year they will release a new game, support it with six supplements over the next year, and then retire the line. The first of these “fourth lines” is called Promethean: The Created (2006) and covers Frankenstein-like monsters and golems. It’s been very well received. 2007 promises to feature a new Changeling as a new fourth line.

In 2006 a much larger change occurred for White Wolf. They were purchased by CCP Games, the Icelandic publisher of the MMORPG Eve Online. This event will likely have a greater effect on White Wolf’s future than any of their successful expansions since 2000. Whether White Wolf is allowed to prosper as a creator of intellectual property–as DC and Marvel comics do–or whether they will be crushed by the high-flying expectations of another industry–as Imperium Games was–remains to be seen.

Thanks to Frank Branham, Allan Grohe, James Lowder, Lisa Stevens, and Steve Wieck for comments on this article. Other information was drawn from White Wolf Magazine, the White Wolf Quarterly, and various interviews and press releases. An extensive but incomplete list of White Wolf games can be found in the RPGnet Gaming Index.