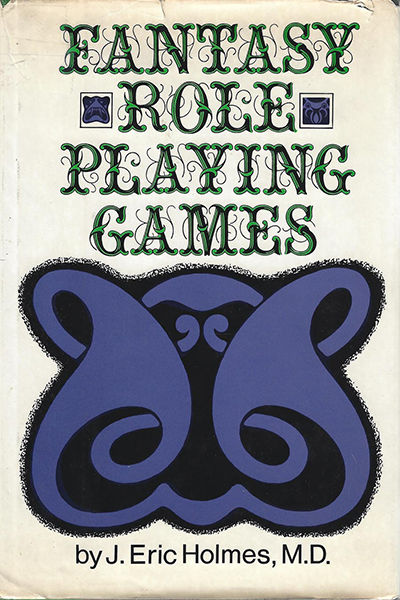

J. Eric Holmes is best known of the creator of the first Dungeons & Dragons Basic Set (1977). However, a few years later he also wrote an introduction to roleplaying games called, quite simply, Fantasy Role Playing Games (1981). It was published by very small presses: Hippocrene in the US and Arms and Armour Press in the UK. Nonetheless, it was an early attempt to push roleplaying games out in the wider world.

The Contents of the Book

Fantasy Role Playing Games is divided into fourteen chapters:

- The Game, Live

- The Player Character

- The Referee’s World

- The Reader Takes a Role

- History

- Dungeons & Dragons

- Empire of the Petal Throne, and Other Dynasties

- Worlds of Science Fiction

- Odd Ball Games

- Man vs Machine

- Little Metal People

- The Magazines

- Are They All Crazy?

- How to Get Started

This is very much an introductory book.

It starts (ch. 1-4) by explaining entirely rudimentary concepts about roleplaying that probably would have been enlightening to people who had never had any experience with RPGs, but which seem very low-level today. The most interesting part of these early chapters is a full introductory dungeon by Holmes. After a brief stop in the origins of D&D (ch. 5), the bulk of the book is then spent outlining the games, miniatures, magazines, and nascent computer games making up the industry (ch. 6-12).

Though much of this probably isn’t of interest to modern readers in and of itself, Fantasy Role Playing Games does remain somewhat interesting for the window that it gives us on the roleplaying industry about five years after its birth. (Though the book is copyrighted 1981, based on the content I suspect it was written in the 1979-1980 timeframe).

What We Learn About History

Fantasy Role Playing Games isn’t a history book, but Holmes does devote a chapter to the topic, and it’s pretty much what we know today: Gary Gygax published Chainmail (1971), which Dave Arneson used to run his Blackmoor game. Arneson then brought the idea back to Gygax who began running Greyhawk adventures. TSR published their work as Dungeons & Dragons (1974). None of this is new, but it’s nice to see the same story that we know told just several years after the fact — especially given the 21st century advent of Chainmail denialists, who insist that Chainmail either wasn’t used or wasn’t important to the creation of D&D.

Holmes also weighs in on the Tolkien debate. Both Rob Kuntz and Gary Gygax claimed in Dragon magazine, that D&D was not influenced by Lord of the Rings. Obviously, Holmes would not have been involved in those decisions, but he offered the same common sense view that most players would have had at the time, saying that D&D’s world “resembles the Middle Earth of J.R.R. Tolkien’s grand epic” and more notably that the “rules of D&D conform to Tolkien”.

Finally, there’s a short mention of the 1979 James Dallas Egbert III disappearance. Here, Holmes affirms what later statistics would also suggest: “the publicity probably only popularized the game”.

What We Learn About the Top RPGs

Holmes doesn’t explicitly talk about the bestsellers of the industry, but he does reveal a lot by what he lists.

He says that Dungeons & Dragons is still the “best” of the roleplaying games, and by giving it a whole chapter, he suggests that it’s the big dog. He also suggests that fantasy is the best-known genre because he lists out a high number of fantasy games, including Empire of the Petal Throne (1975), Chivalry & Sorcery (1977), Tunnels & Trolls (1975), Melee (1977), Wizard (1977), and RuneQuest (1978). He even notes some important supplements like The Arduin Grimoire (1977) and All the Worlds’ Monsters (1977).

Holmes gives a lot of attention to TSR’s games, including Empire of the Petal Throne, which was already fading at TSR by the end of the ’70s. Thus, it’s even more notable that the game that gets the second most attention after D&D is actually Traveller (1977), which was published by GDW. It’s suggestive that Traveler might have been RPG’s #2 game by the time that Holmes was writing.

It’s also notable that Holmes already recognizes science fiction as the second most notable genre for roleplaying games, despite the fact that he only gives extended attention to two other SF RPGs, Metamorphosis Alpha (1976) and Gamma World (1978). Holmes’ recognition is thus probably another clue toward the strength of Traveller at the time.

Today we’d probably note superheroes as the third most popular genre in roleplaying, but none of the major supergames had yet been published when Holmes was writing, so he just lists them as part of the “Odd Ball Games”, which include Superhero ’44 (1977), Boot Hill (1975, 1979), Bunnies & Burrows (1976), and Gangster! (1979).

And that was Holmes’ state of the industry in (probably) late 1979: a scant 14 games, most of which would be largely unknown within a few years.

Holmes’ listing also tells us one other thing: roleplaying games and man-to-man combat were still closely linked. Though En Garde! (1975) is missing from Holmes’ list, he does include Melee and Wizard, which were basically fighting games, alongside Boot Hill, which was just gaining increased roleplaying trappings in its second edition (1979).

What We Learn About the Industry

Holmes also offers some intriguing insights into what the industry looked like at the time.

Most notably, the industry and its fans were much closer at the time. That’s made obvious by Holmes’ discussions of the industry’s magazines, which gives equal attention to professional magazines (Dragon, Different Worlds, Dungeoneer, Journal of the Traveller’s Aid Society, Judge Guild Journal, Sorcerer’s Apprentice, Space Gamer, and White Dwarf) and to top APAs (Alarums & Excursions and The Wild Hunt). The wargaming industry that roleplaying grew out of was largely fan-based, so it’s no surprise that fans would have equal weight in the roleplaying industry in its early days.

And who were those fans? Holmes notes the industry’s biggest demographic when he says “there wasn’t a college in the land that did not support a D&D group”. He also says that the average age of players at conventions is 17 and that “Almost all are men”. A few years earlier, that average age was probably higher, but anecdotal evidence has long suggested that Holmes’ own Basic D&D, and the Basic Sets that followed, were what began to drop the age of D&D players.

Holmes’ book also suggests the coming of something new to the industry: defensiveness. He spends an entire chapter (ch. 15) defending the hobby and its players in response to his own rhetorical question, “Are they all crazy?” He gives away the reason for this when he says that he frequently has to answer another question from peers: “Isn’t that the game where the students from Michigan were playing in the steam tunnels and one of them got killed.” Though the answer to that question is “No and no”, the James Egbert incident marked the beginning of the moral outrage against D&D that would only spread in the ’80s. Holmes’ book thus marks one of the first responses to that outrage, a role that would be taken up more fully by Michael Stackpole, starting with his article “Devil Games? Nonsense!” in Sorcerer’s Apprentice #14 (Spring 1982).

What We Learn About D&D

Holmes’ insights into the industry in Fantasy Role Playing Games are somewhat incidental, but he’s quite explicit in his discussion of D&D, and it gives an intriguing look into how the game was being played in the late ’70s.

He said that Gygax compared the D&D world to “a boom town in the Alaskan gold rush. The value of everything is inflated, money is cheap, adventurers are bringing gold and jewels out of the dungeons by the bucketful and magical items abound.” Player characters join this ecosystem because they’re “motivated almost entirely by greed“.

When those greedy characters delve into their dungeons, however, they should be prepared for death. Holmes suggests that beginning players should have several characters because some will die; in fact, he says that “Some referees feel the game is a failure if half the player characters are not killed in each game!” If this sounds competitive, it is; he notes that in a good campaign, the players should get together “to plot” in between adventures!

Though Holmes says that players enjoy the game to solve problems and to develop their character, this is all done through the lens of a dungeon exploration. And, that exploration occurs in a very slow, logistical, and methodical way. In the sample AP that Holmes provides, his players are literally advancing one footstep after another, describing every small movement and how the characters are examining, poking, and prodding everything within the dungeon.

Holmes’ sample dungeon also offers insights into what players faced at the time. It’s full of tricks (like slamming doors), of secret rooms, and of unique traps (and monsters, of course). But, Holmes emphasized, those various encounters always needed to give the characters some way out, if they were smart, clever, or lucky enough.

Holmes’ D&D is pretty much the definition of a dungeon crawl, but Fantasy Role Playing Games goes a step further and details what that actually means!

What We Learn About Holmes’ Basic

Finally, we come to Holmes’ own contributions to the D&D game, and here there’s unfortunately not a lot of insight in Fantasy Role Playing Games. Holmes talks shockingly little about the Basic D&D game that he actually wrote.

He does give a pretty standard description of its genesis, saying, “In 1974 I persuaded Gygax that the Original D&D rules needed revision and that I was the person to rewrite them. He readily conceded that there was a need for a beginners’ book and ‘if you want to try it, go ahead.'” Holmes recounts going through the original three rule books (1974) and the first two supplements (1975). He notes that “Greyhawk [was] the greatest help”. Holmes also says that he tried “to use the original words of the two game creators as much as possible” in order to present “the game as it was first produced”.

By the time Basic Fantasy Role Playing came out, the AD&D system (1977-1979) had also been released. Holmes talks a bit about the differences between that and his game, saying that in AD&D, the books are “much more extensive and detailed”, the “[c]ombat is more complicated”, “calculations are much more difficult”, and “the number of die rolls has nearly doubled”. He says that moving from Basic D&D to AD&D will be “a moderate ‘culture shock'” and regrets that AD&D did not “grow smoothly and naturally out of the Basic Rules”. In fact, he considers this such a big problem that he tells readers not to purchase his Basic Set if they plan to play above level 3!

However, the most interesting information about Holmes’ Basic D&D may be his listing of inspirational reading for D&D, which is practically his own Appendix N: He lists J.R.R Tolkien, Fritz Leiber, Robert E. Howard, L. Sprague de Camp, and Jack Vance as general inspirations for the game, and notes that his own games have drawn from A. Merritt, Andre Norton, Clark Ashton Smith, Lord Dunsansy, Edgar Rice Burroughs, and H. Rider Haggard; Dunsany and Haggard are the two authors on Holmes’ list missing from Appendix N, so they may be worth exploration for fans looking to understand his particular style of gaming.

Conclusion

Unfortunately, J. Eric Holmes Fantasy Role Playing Games doesn’t offer that much insight into the man himself, designer of one of TSR’s foundational D&D games. It does, however, give a great view of the industry circa 1979 or so, albeit amidst much explanation that’s probably somewhat dull to an existing fan of the genre.

This article was originally published as Advanced Designers & Dragons #12 on RPGnet. It followed the publication of the four-volume Designers & Dragons (2014) from Evil Hat, and was meant to complement those books.