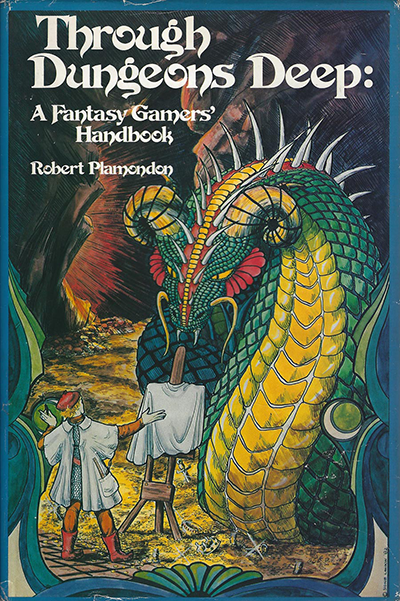

Through Dungeons Deep: A Fantasy Gamers’ Handbook (1982), by Robert Plamondon, is a book that was written as an introduction to the roleplaying field. It offers advice on playing and gamemastering as well as designing campaign worlds. There’s also a listing of fantasy roleplaying games, magazines, and APAs at the end.

The book was put out in the day by Reston Publishing, who was one of the big publishers trying to push into the increasingly profitable roleplaying field in the ’80s. Their most notable publications were High Fantasy (1981) and RuneQuest (1982). Through Dungeons Deep was likely seen as a way to introduce readers to the hobby, in order to get them buying Reston’s other RPG books.

Plamondon has recently reprinted Through Dungeons Deep as a self-published book, so it’s readily available in a paperback or Kindle edition.

The Contents

Through Dungeons Deep is somewhat of a mishmash. Plamondon got his start writing articles for Dragon and eventually decided that his TODO-list could be the table of contents of a book. More properly, it’s the table of contents of a few different books, but they’re all intriguing.

The major sections of Through Dungeons Deep are “How to Play”, “Game Mastering”, “The Complete Campaign”, and a set of “Appendices”. The whole book is just over 300 pages, with the player’s section taking up slightly more than a third of the book and the world-design section a bit less.

What We Learn About History

One of the most interesting aspects of Through Dungeons Deep is that it was written during a time of transition in the roleplaying industry, when the old-school dungeons of the ’70s were turning into the plotted adventures of the ’80s. Philosophically, Through Dungeons Deep plants itself firmly in the ’80s, saying things like “[in an RPG] everyone works together” and “role playing is essential to a good fantasy game”, but the most interesting part of the book is actually spent guiding players through the tropes of old-school dungeon play.

This chronological tension is the most obvious in Plamondon’s listing of sorts of games. He says that RPGs can have one of four focuses: “Dungeon Adventure” (which he called “the Shoot and Loot scenario in underground settings”), “Overland Adventures” (“Shoot and Loot games in the great outdoors”), “Campaign Games” (showing “the importance of society”), and “Role playing” (where Plamondon says, “It’s surprising how few games mention it”). This distinction clearly shows the whole industry at a turning point.

There’s another transition obvious in Through Dungeons Deep: from the rules-light approach of games like OD&D (1974) to the rules-heavy approach of AD&D (1977-1979), which was designed to facilitate tournament play, and so required a much stricter and more precise rules system. Plamondon, like many early players, was clearly chafing at the new rules, saying that you “don’t really need rules at all”; later, when talking about Gary Gygax’s statement that players shouldn’t change a game’s rules, Plamondon even more bluntly says: “I think this is hogwash.”

This is all surprisingly in tune with the High Fantasy RPG that Reston that was then publishing, which leads with the statement: “This is not a book of rules. The actual rules consist of only a few pages.” Could it be that the editor for Reston’s High Fantasy and Chaosium books, alongside Through Dungeons Deep, actually knew their way around the roleplaying industry and was trying to present a consistent vision? It somehow seems unlikely that any of the bigger publisher who dove into roleplaying publishing in the early ’80s knew much about the subject, and sadly the answer here is lost to the tides of time.

What We Learn About the Evolution of Play

The players section of Through Dungeons Deep falls on the old-school side of the chronological divide, and that makes it the most intriguing section in the whole book (and the one most intriguing to modern historians). That’s because it’s practically an OSR Handbook, suggesting how D&D (other other RPGs) were played at the dawn of the hobby: something the OSR movement has been working to recreate.

Sections include discussions of how to outfit your characters, how to explore dungeons, and how to gather loot. Unless you’re playing an OSR game, this all reads a bit alien — and I’m not even convinced that the typical OSR games plays quite as old-school as this. In fact if this section reads like anything, it’s Torchbearer (2013), a modern design trying to recreate old-school gaming via resource-management systems that was very successful in its first edition due to its well designed and nostalgic play, and which just doubled-down on its success with a $350,000 Kickstarter for a second edition. In any case, if you want to play super OSR, here’s how.

The section on gathering loot is probably the most delightful. It is so foundationally old-school that it almost reads like satire. I’m not sure any modern player could imagine playing D&D like this: “Bags of coins are easy; they are first hit with an arrow, then slit with a spear blade, then the coins are put in another bag with a trowel. Loose coins are disturbed with arrows, then a spear, then troweled into bags.” The fact that it’s almost unimaginable in the modern day, except maybe to the most OSR of the OSR, is why this is particularly fun historical (and OSR) resource.

Scattered throughout this section are more tidbits on how old-school games were different, from carefully constructed mathematical systems for dividing up loot to discussions of how to use hirelings and henchmen. Another delightful bit focuses on the more antagonistic inter-party conflicts of the early days (running at odds with Plamondon’s statement that “everyone works together”). At one point, Plamondon states: “after you kill a couple of thieves, the other players will leave your character’s money alone”.

For either historical or OSR interest, the player’s section of Through Dungeons Deep is pure gold (that must be disturbed by arrows, then spears, then troweled into new bags).

What We Learn About The Evolution of GMing

In comparison to the wonderfully insightful player section, the rest of the book, covering first GM advice, then world-design advice, is just OK. There is still some historical interest, because you can again see the industry in transition as Plamondon talks about different sorts of campaigns: “role playing”, “war gaming”, “power gaming”, “the silly game”, and “storytelling”. Really, it’s Plamondon’s own GNS theory: wargaming leans toward gamist play, power gaming toward simulationist play, and story telling toward narrativist play, but it’s seen from a different era, when wargaming was a much larger part of the industry.

Beyond that, you could find much of the design advice in any number of more modern books. The most modern-feeling element is an emphasis on ecology in making dungeons (and campaigns) that make sense. You can certainly find this in old-school games, in what Grognardia called Gygaxian Naturalism, but it’s even more of a focus in the campaign worlds that grew beyond dungeons in the ’80s, so seeing it here suggests the GMing advice comes from the other side of the chronological old-school divide.

What We Learn About The Industry

Through Dungeons Deep finishes up with a ludography of the industry’s then-current FRPs. This sort of overview of roleplaying games from a set point in time is always intriguing, both for what the “top” games of the era were and for what someone though of them. In Through Dungeons Deep, the most surprising thing is how obscure at least half of the games are.

Plamondon covers: Adventures in Fantasy (“a number of production mistakes [but the game itself is] pretty good”), Arduin (“many interesting ideas present in abysmal form”), Chivalry & Sorcery (“the enormous amount of text is a little daunting, but isn’t as bad as it looks”), D&D (“depend[s] heavily on stereotyping”), Dragonquest (no comments), The Fantasy Trip (“I was struck by the clarity of writing and the simplicity and logic of most of the rules”), High Fantasy (“simple and easy to learn … a good base for a campaign”), Land of the Rising Sun (no comments, RuneQuest (“its attention to role playing is second to none”), and Tunnels & Trolls (“easy to learn, fast, and inexpensive”).

The other particularly interesting thing found in the appendices is a look at RPG magazines that gives equal time to the amateur APAs. That was certainly a different era, though in the modern day, the commentary and discussion role of APAs has been largely replaced by forums and Facebook groups.

Conclusion

Through Dungeons Deep doesn’t give any specific insights to the history of companies within the roleplaying world, like reading J. Eric Holmes’ Fantasy Role Playing does, but it does provide insight into a period of roleplaying play, the exact period that the OSR is now working to replicate, and as such it’s both an intriguing history book and a great HOW-TO book for OSR play.

This article was originally published as Advanced Designers & Dragons #30 on RPGnet. It followed the publication of the four-volume Designers & Dragons (2014) from Evil Hat, and was meant to complement those books.