Roleplaying fandom is a powerful thing. When a game is ascending, it can support that rise and bring it to new heights. The flurry of fanzines in the ’80s and ’90s and the advent of community content starting in the late ’10s all speak to this power. Actively supported RPGs benefit greatly from fandom’s parallel publications.

But roleplaying fandom may have even more power when a game is faltering, with its official publications growing scarce. Fanzines, other fan publications, and fan conventions have often been the only throughline as an RPG powers down its official publications, jumps from company to company, or both. That’s the story of how the Hero Auxiliary Corps supported Champions (1981) from Hero Games’ small-press beginnings through their merger with ICE, and how HIWG kept the flame of Traveller (1977) alive as first GDW, then Imperium Games went out of business.

But even these notable fan organizations eventually faded: HAC as they found wider success and HIWG as they lost the competition with online forums. But one fandom may have done even more to ride the waves of its game’s crests and troughs. That’s the Gloranthan fandom, who has risen so far that today they own the setting and its core games, RuneQuest (1978) and HeroQuest (2000).

More of the story of Gloranthan fandom can be found in The Moon Files: The Reaching Moon Megacorp (2024), which has been published by Tentacles Press as a chapbook in print and as a PDF and will appear in Designers & Dragons: The Lost Histories, but not for a few years. This article focuses primarily on the publishing power of Gloranthan fandom through its periodicals and con publications. A somewhat shorter and older discussion of RuneQuest’s periodicals may also be found as “The Gloranthan Fanzines: 1976-Present” in Designers & Dragons: The ’00s (pp. 58-59).

RuneQuest and Gloranthan creators Steve Perrin and Greg Stafford led the way for Gloranthan fandom with their publications of zines in the APAs Alarums & Excursions (1975-Present), The Wild Hunt (1976-1995), and The Lords of Chaos (1977-1981). Perrin was writing for A&E before RuneQuest was even a consideration, meaning that he had deep ties to the larger fandom of tabletop roleplaying.

But for the real foundation of Gloranthan fandom, one should probably look toward England. There’s a reason that Gloranthan fandom first began publishing in the UK, and not in the United States where Perrin, Stafford, and Chaosium were all located. That reason was Games Workshop (GW), who first imported Dungeons & Dragons (1974) into the UK and then created even closer ties with a variety of other games such as Call of Cthulhu (1981), Paranoia (1984), RuneQuest, Stormbringer (1981), and Traveller.

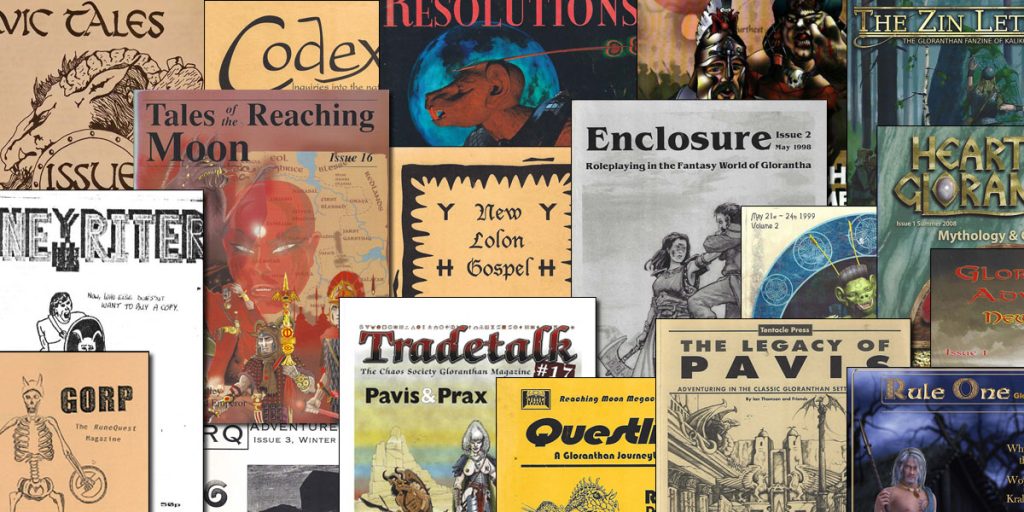

Games Workshop imported these games, reprinted them, featured them in White Dwarf (1977-Present), and hyped them at GamesDay, granting them an outsized impact and enthusiasm across the pond. As a result, the first three fanzines dedicated to RuneQuest all appeared in England: Neil Smith’s little-known RuneRiter (1986-1987), the legendary Pavic Tales (1987-1989) by the RuneQuest boys, and most importantly David Hall and friends’ Tales of the Reaching Moon (1989-2002).

RuneRiter and Pavic Tales perhaps represent the stories of fandom at a game’s height, as they were released not long after the publication of RuneQuest 3 (1984) and overlapped with a GW reprint of the game (1987) that ensured that the game remained reasonably priced in the UK. But, bad times were coming by the time Tales of the Reaching Moon appeared on the scene. The relationship between Chaosium and their new RuneQuest publisher, Avalon Hill, was fraying and as a result Chaosium was getting out of the Gloranthan business. Even the art was deteriorating in new products as Avalon Hill cut corners. “Ruined-Quest?”, a famous article outlining these problems and more, appeared in Tales of the Reaching Moon #5 (Spring 1991).

If ever there was a fannish organization that helped support its game through hard times, that was the fandom of Tales of the Reaching Moon. Over its 13-year run, the so-called Reaching Moon Megacorp published not just 20 issues, but also several supplements. They also created a community that literally spread across the English-speaking world. That began in Tales itself but also in a series of conventions, the first of which was Convulsion of the Trillion Tentacles (1992). More conventions followed, called Convulsion then Continuum in the UK and called RQ-Con then Glorantha-Con in Australia, Canada, and the United States. (Germany also had its own history of RuneQuest conventions, dating back to 1990, and that fandom would join the one that grew out of the Reaching Moon Megacorp in its later years.)

By all rights, the ’90s should have been the worst time ever for RuneQuest and for Glorantha, as first its creators abandoned the game and the world, and then the game went out of print entirely (with Avalon Hill eventually being gobbled up by Hasbro). Instead, it was a Golden Age, and that was almost entirely due to RuneQuest fandom—plus a brief Renaissance of RuneQuest material from Avalon Hill in 1992-1994, but that too was supported by RuneQuest fandom.

The fannish community created by Tales of the Reaching Moon and the ever-growing wave of conventions resulted in the production of many other fanzines. This Golden Age of Gloranthan fandom lasted for approximately a decade, depending on where you decide to mark the edges, with 1993-2004 being the height.

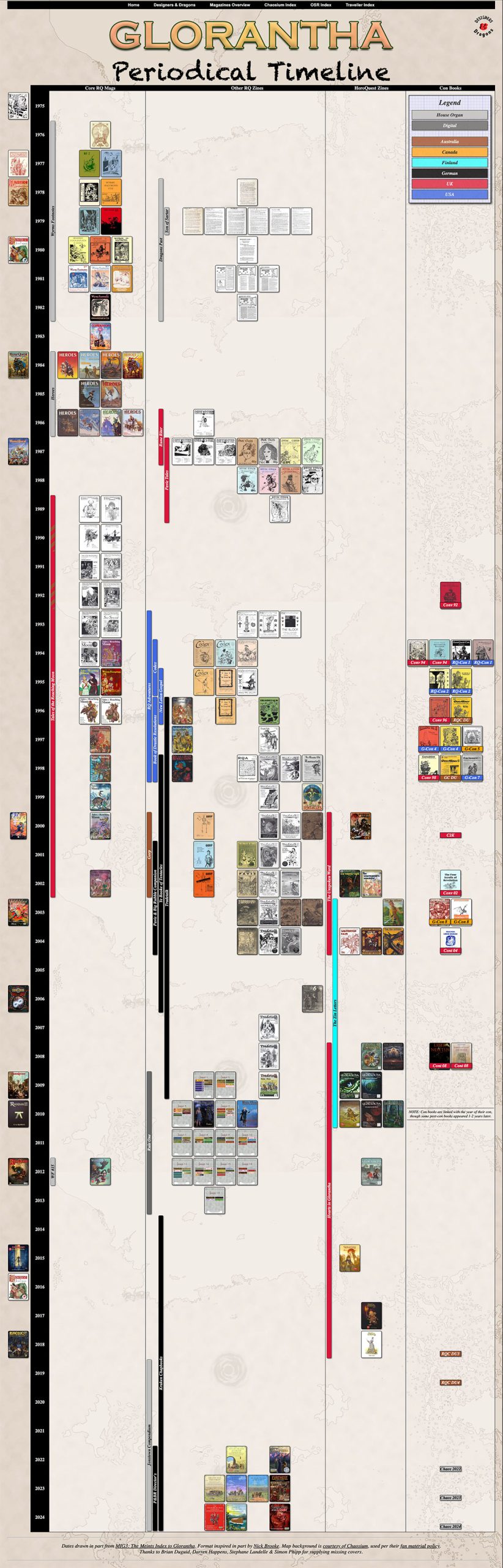

The following graphic lays out the entire story of Gloranthan fandom, as seen through its periodicals and conventions. It can be found in more readable HTML form here.

This period from 1993-2004 saw the advent of four new RuneQuest fanzines in the United States: RQ Adventures (1993-1998), Codex (1994-1995), New Lolon Gospel (1995-1996), and The Book of Drastic Resolutions (1996-1998), which were shockingly the first-ever American fanzines created for the American games. (Obviously there had previously been official magazines from Chaosium and Avalon Hill.) It saw the German RQ-Society begin producing English-language books as well, resulting in another three periodicals, Tradetalk (1996-2009), Ye Booke of Tentacles (1998-2006), and the Pavis & Big Rubble Companion (2001-2004). Meanwhile, there were 14 English-language conventions focused on RuneQuest and Glorantha, most of which tended to have at least a little original content in their program books, and many of which also were supported by fund raising books or complemented by post-con compilations that were just as much periodicals as some of the regular zines. The RuneQuest community as seen through its zines and conventions in this decade was so strong that it could even support some good-nature joke publications such as the Australian Gorp (2000-2002, but rumored to be reprints of books from 1982-1983).

It’s somewhat tragic that in the ’00s this rich fandom community was mortally wounded, though it was for the best of reasons: Greg Stafford brought Glorantha back home to Chaosium (and later to his new company, Issaries) and published a new game, Robin Laws’ Hero Wars (2000), which was later updated as HeroQuest (2003). It was a vastly different game than RuneQuest that changed the world’s play style from simulation to narrative. Game systems such as Champions and Dungeons & Dragons have received serious criticism for much less dramatic changes in gameplay: ones that changed fundamental mechanics but not the style of play. The change from RuneQuest to Hero Wars was much more. It didn’t receive the same criticism as Champions: New Millennium (1997) or Dungeons & Dragons 4e (2008) because it was seen as the only option at a time when the IP rights for RuneQuest were muddled. Nonetheless, it marked a stepping-off point, as an aging fandom came to the conclusion that their game was gone forever.

HeroQuest did generate its own fandom, some of it carried over from Tales’ RuneQuest fans. Yet more fanzines such as The Unspoken Word (2000-2004), The Zin Letters (2003-2010), and Hearts in Glorantha (2008-2018) appeared as a result, the earliest of these HeroQuest zines overlapping with the end of the RuneQuest fandom Golden Age.

But 2005 would mark the true end of that Golden Age as the other shoe dropped. In 2000, the beginning of the end of the Golden Age had been marked by the publication of Hero Wars and the fact that it meant that a new Glorantha publisher was in town. The end came in 2005 with Glorantha’s Fan Policy, which tightened Issaries’ control of their game and game world. By preventing the creation of “derivative works” without a license, not even allowing fandom to paraphrase existing content or redraw existing maps, the Fan Policy ensured that the previous era, when fans had largely controlled the fate of Greg Stafford’s world of Glorantha, was.

The first fan-produced ‘zine exclusively about Glorantha appeared in 1986. From there on, at least two issues of a fanzine appeared in every year through 2004, at which time rumors of the upcoming Fan Policy put things on hold through 2006. The three most prolific years of fanzine production saw seven different ‘zine issues published; the wide scattering of those three years shows how long the RuneQuest community has been strong. 1987 saw seven total issues of the first two RuneQuest fanzine, RuneRiter and Pavic Tales. 2002 showed a community in transition, but one that remained strong: the final issue of Tales of the Reaching Moon was mirrored by two issues of the Hero Wars–focused Unspoken Word, with Pavis & Big Rubble Companion, Tradetalk, and a reprint of Gorp also appearing. Then 2010 saw Hearts in Glorantha, its sister magazine Gloranthan Adventures, and The Zin Letters all make appearances, alongside four issues of Roderick Robertson’s online magazine, Rule One (2009-2013). If you count the periodical publications of the conventions, the numbers stack up even higher, especially in 1994-1998, which saw 1-3 Gloranthan conventions running every year!

That third height of fanzine production in 2010 also demonstrates that things are ever changing and that fandom constantly responds. Though the Fan Policy had caused a lot of fandom to stutter to a halt, Hearts in Glorantha and Gloranthan Adventures were both published under license from Issaries, as was now required, which resulted in a high degree of professionalism. But, Hearts in Glorantha was the last standing Gloranthan fandom when its last two issues appeared in 2017 and 2018, ending a tradition that had dated back to 1986.

But things are still changing today, and fandom continues to respond. In 2019, Chaosium (back in control of Glorantha and RuneQuest, and now under the control of previous fans) offered fandom a new channel for their creativity: the Jonstown Compendium, a community content program of the sort initiated by the Dungeon Masters Guild for D&D. It dramatically lowered the barriers of entry for fandom creativity, while allowing for the production of very high quality publications.

To date, 430 titles have been released for the Jonstown Compendium, 64 of them with print-on-demand (POD) options. A shelf of just the print books from the Jonstown Compendium is at least three times the size of a the print RuneQuest books released by Chaosium in the same time period.

The periodical history of Gloranthan fandom may be done (perhaps) but if so it’s only because of the ease with which an individual fan can release their own vision of Glorantha in the modern day.