This is the final entry from the Designers & Dragons Platinum Appendix that was commissioned by a patron interested in seeing the history of a particular organization. To be specific, it was commissioned by my own gaming club to talk about the history of that club. So consider this an “About the Author”, and a look at a 25-year-old roleplaying group.

This article was originally published as Advanced Designers & Dragons #7 on RPGnet. It was written for inclusion in Designers & Dragons: The Platinum Appendix (2015).

Gaming groups can survive for decades, holding together friends who might otherwise have drifted apart. The RuneQuest Mafia is one of those — though its members have also touched the larger roleplaying industry.

Bringing Together the Mafia: 1987–1990

The story of the RuneQuest Mafia begins with Eric Mehlhaff — a student at UC Berkeley who decided to form a roleplaying club around 1987. He had to register the club at Sproul Hall on the Cal campus and to gather four students to sign up as officers; afterward, he could reserve rooms for gaming in buildings on campus. He also got one other benefit: permission to hang a permanent sign at Berkeley’s Sather Gate, on the bridge over Strawberry Creek. The painted wooden sign that he posted read “Berkeley Campus Adventurers Club,” the club that would be the immediate predecessor to the Mafia.

During BCAC’s first two years, rooms were reserved and games were played. The club’s gaming schedule was GURPS (1987) heavy in those early days, but Mehlhaff also ran a short campaign for a new game that we’ll soon return to: Ars Magica (1987). The larger story of BCAC lies outside of the history of the Mafia, but a few of the club’s first members would eventually become Mafia members too — among them Matt Harris, Eric Mehlhaff, Alex Purl, and John Tomasetti. The fall of 1988 brought one other early member of note: grad student Eric Rowe, who would soon become the nexus of the Mafia.

In the Fall of 1989 more future Mafia members came on stage. Shannon Appelcline (then Shannon Appel), Dave Pickering, and Dave Woo were all freshmen, newly arrived at Cal, while Bill Filios was another newcomer to the BCAC community. Yet more future Mafioso trickled into BCAC in the next year, among them Donald Kubasak, Doug Lampert, Matt Seidl, Dave Sweet, and Kevin Wong. Some would find their way to the BCAC from that wooden sign over Strawberry Creek, while others were brought into the club by friends.

These histories often discuss how game stores are a crucial locus for roleplaying — as places to find new games and new releases alike. And they are. The history of the Aurania Gang tells how game stores were crucial to the western LA gaming scene, while the histories of Columbia Games and White Wolf talk of the dangers of abandoning the distribution chain.

However college gaming groups were at least as important in the ‘70s and ‘80s. They’re full of wild creativity — of people at the start of their lives daring to imagine anything. ICE, Lion Rampant, Midkemia Press, Palladium Books, and Jennell Jaquays’ Fantastic Dungeoning Society all grew out of college gaming groups.

College is also the place where gaming tastes evolve — where players learn about new RPGs, extending their horizons beyond the scant games they played in high school. Retail stores might still be crucial to this evolution, such as when Matt Harris found Ars Magica (1987) at Don Reents’ Games of Berkeley, but it was on the Berkeley campus that Eric Mehlhaff actually brought that game into play.

When the future Mafia members came to Berkeley in 1989 and 1990, they’d almost all been introduced to roleplaying by Basic Dungeons & Dragons; most of them arrived through Tom Moldvay’s edition of the game (1981), but Sweet remembers the blue cover of J. Eric Holmes’ game (1977) and Wong remembers the more professional boxed set produced by Frank Mentzer (1983). About half of them had played other games, including Phoenix Command (1986), Paranoia (1984), Call of Cthulhu (1981), Stormbringer (1981), Champions (1981), and Shadowrun (1989). However, D&D in its several forms had been the main course, and they were ready for something new.

We now return to Fall 1989 and the initial influx of Mafia members. At the time, BCAC reserved several rooms in Dwinelle Hall — one of the most labyrinthine buildings on the Berkeley campus. Roleplayers would arrive in the building around noon each Saturday and choose games à la carte. One game would run from lunch to dinner, and then another would run from dinner until late in the evening. Players could wander from one room to the other between the sessions and play with a different group each time. Eventually, cliques would develop, but they would take time.

During that period, there were two games of importance to the Mafia.

I was thinking of taking Gentle Gift, so I can sneak up on people.

Dave Pickering, Ars Magica game

The first was Matt Harris’ Ars Magica game, the BCAC’s second such campaign. As an early independent RPG, Ars Magica offered very different play from the D&D norm. Players took on the roles of characters at vastly different power levels — including guard-like grogs, a variety of companions, and of course wizards. They also participated in stories that weren’t just dungeon crawls. Harris’ campaign was short-lived, but “Gilliam’s Keep” — named for Filios’ grog character — showed the future members of the Mafia that there was more to roleplaying than D&D. It would also lead to many other Ars Magica games over the years, one of which would be published by White Wolf.

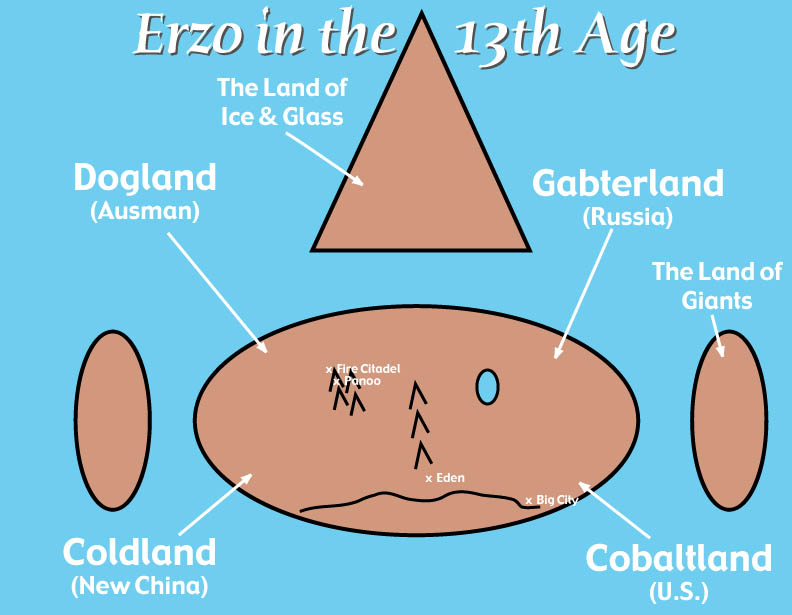

The second was Eric Rowe’s ErzoQuest campaign, which would become the group’s defining game. ErzoQuest was a RuneQuest (1978) game set in an original world that Rowe had created. The inventiveness of the world melded well with Rowe’s star GMing. He was adroit at thinking on his feet — to the point where he was sometimes mocked for coming to games unprepared. But that was possible in part because of the extensive time that Rowe had spent designing Erzo: he began writing the world’s underlying mythology in Summer 1989 and was working on a massive 32-page map of the world around the time that the Loma Prieta earthquake shattered the Bay Area on October 17, 1989. Even today, Rowe still has a head full of Erzo lore he’s never committed to paper.

Like the world of Talislanta (1987), Erzo was an innovative setting that deviated from standard fantasy tropes. Humans were a dying race, while the rock-like Vikul were the inheritors of the world. Other major races included a warrior race of giant rabbits called the Gabter, the plant-like Rezla, and the draconic Jiliroth. Beyond that, the story of Erzo was epic. Rowe imagined a world history that moved through 15 major eras, one for each of the major runes. In this first campaign, Erzo stood at the divide between the 5th and 6th ages. As the Age of Civilization approached, empires rose and fell, and the characters played major roles in those happenings.

That was the first chapter in the history of the RuneQuest Mafia. A group of old-timers including Harris, Mehlhaff, Purl, and Tomasetti were joined by newcomers like Appel, Filios, Pickering, and Woo to play a transformative game run by Rowe. And then in Spring 1990 their numbers began to swell thanks to Kubasak, Lampert, Seidl, Sweet, Wong, and others.

And that was just the beginning.

Erzo Days: 1990–2004

Harris’ Ars Magica game ended in the Spring of 1990, but new roleplaying options immediately appeared within the large, vibrant BCAC group. Many of the future Mafia members moved over to an AD&D 2e (1989) game run by Tomasetti, but some opted instead for yet another Ars Magica game, running across the hall. Saturday gaming days were also growing in length: the day’s two roleplaying sessions were sometimes followed by a middle-of-the-night Battletech (1985) game and then a trip to Berkeley’s Open Computer Facility, where gamers could play tournament Xtrek games until they were kicked out by cleaning staff at 5am — about 17 hours after the gaming day began.

Meanwhile Erzo was ramping up in popularity. Early histories of roleplaying often tell about primal roleplaying campaigns growing vast due to their success, and that’s exactly what happened with Erzo. At its height, it had somewhere between 12 and 20 players — arranged at not one but two large tables.

He was born a farmer, but died a not-very-good-warrior.

Dave Pickering as the Vikul Tok, ErzoQuest game

Following that summer, Erzo’s numbers settled down to a more manageable number. This was in part because some of the old guard was fading away: Harris moved on to UCLA while Purl joined the army. A bit later, Lampert headed back east — forever costing the group its rules lawyer, who knew where everything was in the rulebooks. As players faded away, the remaining members of Rowe’s Erzo campaign were gelling into a coherent whole — more likely to play the same games together, rather than splitting up into the larger BCAC community. Because of their strident love for the Erzo campaign, they were now (at last) named the RuneQuest Mafia by another clique that developed within the BCAC — one that the Mafia in turn named the Chaos Gamers.

Around this time, one of the last members of the Mafia to join during college days showed up: Chris Van Horn. His late arrival was probably why he alone moved effortlessly between the two cliques. He was the taunted-and-teased baby of the group for years, because in college a year or two feels like it makes a difference.

Erzo continued into 1991, and then was put on hiatus while Rowe worked on his thesis. When it returned, the players created new characters, but continued with the same storyline, which eventually reached its epic conclusion. It was the first of three Erzo games that Rowe ran over the years. In the late ‘90s a second Erzo campaign was set in the Age of Movement, where most of the players played a blink-dog-like race called the Lapadors. The last Erzo game ran from 2001–2004 and was set in the Age of Cold. Snowmen and yeti joined favorite races like the Gabter, Jiliroth, and Vikul. Fifteen years after Rowe ran his first Erzo game, this final campaign offered another epic conclusion to the group’s most long-running game.

During these years, from 1990–2004, there were many other games. Ars Magica was the next most important. Though it faded away from BCAC’s Saturday gaming, it reappeared on Friday nights thanks to Dave Martin, a recent graduate of UC Davis who met Appelcline and others through the Ars Magica Mailing List. He was instrumental in the creation of a new “St. Nerius” campaign that ran for just three months in 1991. It was followed by the long-lived Roman Tribunal campaign (1991–1993), the fleeting Nature’s Teeth campaign (1993–1994), and after a few years’ hiatus, the Prospectus Locus campaign (1998–1999). All of these later Ars Magica campaigns were run in a full troupe style, with multiple GMs coming together to create a joint story; Appelcline, Filios, and Van Horn were usually the leads.

Party is just trap backwards with a ‘y.’

Dave Woo as the Criamon Risus, Ars Magica game

However, it was more typical for one GM to maintain control of a game, and that one GM was most frequently Eric Rowe. Over the course of a decade and a half he also ran a long-lived MERP (1984) game, two Gloranthan RuneQuest campaigns, and an “Accursed” AD&D 2e campaign. One of the Gloranthan games ran on Sundays, meaning that a RuneQuest Mafia member could game from Friday night through Sunday evening if he wanted.

Other GMs contributed games of their own, including: a few King Arthur Pendragon (1985) campaigns and a fatally short-lived Hawkmoon (1986) game by Appelcline; a DragonQuest (1980) game by Filios; Boot Hill (1975), Rolemaster Pirates (1982) Pirates, and Star Wars (1987) games by Pickering; and Mechwarrior (1986), Star Trek: The Next Generation (1998), and DC Heroes (1985) games by Wong.

Most intriguing about the RQ Mafia’s list of campaigns over the years is that Wong is the only GM who’s successfully run a game that originated later than the group’s origin date of 1989. The group has certainly embraced new versions of classic rules — for example moving from the original Ars Magica (1987) to fourth edition (1996) over the course of six or more campaigns. However the group’s fundamental ideas about roleplaying seem to have become set when it started playing at Berkeley. It makes one wonder how important nostalgia is for a long-lived group.

Throughout those dozens of campaigns and across those 15 years, the Mafia evolved. The biggest changes came when the core members of the group left UC Berkeley, a process that began as early as 1993. For a few years, the Mafia worked with younger Cal students to try and keep BCAC registered every semester. By 1994 or 1995 they gave up, retreating off campus; for a long while afterward the games were held in Appelcline’s apartment. They later moved on to apartments first shared by Wong and Kubasak, then Rowe and Kubasak. Still later, Pickering’s basement was a Saturday gaming space for a while.

Sadly, the larger BCAC group faded away within a few years of the Mafia’s departure from the campus.

Many college gaming groups die as college days end, but the Mafia continued on because many of the members stayed in the Bay Area — in large part because most of them either studied computer science or else moved into the computer field. Some members moved south to Oakland, Fremont, or San Jose, but they continued to game; Berkeley would remain the nexus of the group until at least the late ‘90s.

However, as Cal days came to an end, there were more departures as well. Filios moved to Iowa when his wife was offered a professorship there, while Seidl moved on to grad school in Colorado. Van Horn largely faded away, in part due to his participation in archaeological digs. Tomasetti moved to Sacramento, and Woo returned to his native southern California.

My advantage is that I don’t have a plan so we can’t be foiled by it failing.

Shannon Appelcline as Filbert the Fighting Bard, AD&D 2e game

Surprisingly, they all returned at times. Filios would visit for major events; Seidl would stop by in later years when his job brought him to the Bay Area; Van Horn would occasionally return for six months or a year at a time; and Tomasetti would travel an hour and a half for Erzo games. Finally, Woo would make a more full return after about two years.

It showed how the group was becoming as much about friendships as gaming.

Eric Fulton was the last member to join the group in this era, showing up in 1997. Chris Van Horn finally stopped being the new guy as that title was transferred on to a new recipient, who held it for about a decade. However Fulton didn’t let that stop him from running games of his own, including Dark Sun (1990) and Middle-earth games, both of them using the D&D 3E (2000) rules.

At heart, a young gaming group is about games, and the RQ Mafia played lots of them in the ‘90s and early ‘00s, before life finally started catching up.

The Inevitable Publishing Interlude: 1992-Present

During the ‘70s, it was easy to break into the gaming industry because publishing standards were low: anyone with a typewriter and a mimeograph machine could produce books that were similar in quality to those published by professional companies. In the ‘80s, professional publishers’ standards went up, but then Desktop Publishing arrived, allowing a new wave of fans to enter the industry. In the ‘90s, publishing standards were climbing even higher, but a new entry point appeared for the industry: the internet.

The RuneQuest Mafia never fully jumped into publishing, but throughout the ‘90s, members of the group came together to work on professional publications. It all started in 1990, when Shannon Appelcline took over the Ars Magica Mailing List from Dave Martin. By chance, this put him in direct contact with Ars Magica designer Mark Rein•Hagen. As Appelcline had been an aspiring author since writing Doctor Who-inspired short stories in grade school, he took this the opportunity to pitch a gaming book to Rein•Hagen: a supplement about Mythic Europe Rome, based on the Mafia’s Roman Tribunal campaign.

Tribunals of Hermes: Rome (1993), was co-authored by Shannon Appelcline and Chris Frerking — a member of the group in the early ‘90s who only attended the Friday night Ars Magica games. It was the gaming book that most fully belonged to the Mafia as a whole, as it’d been written by two of its members and based on one of their campaigns. The “authors’ dedication” was also a who’s who of the group’s Ars Magica players at the time, including: Philip Brown, Bill Filios, Scott Gier, Philip Gross, Donald Kubasak, Doug Lampert, Dave Martin, Doug Orleans, Don Petrovich, Dave Pickering, Eric Rowe, Matt Seidl, John Tomasetti, Dave Woo, and Kevin Wong. There were some changes between the campaign and the book, which made the setting less pragmatic and more fantastical; then, White Wolf asked Appelcline to add more demons. Still, it was an interesting mirror of two and a half years of play.

A year after the publication of Tribunals of Hermes: Rome, two events led a few members of the group to more work in the industry.

The first major event was Appelcline and Rowe’s attendance of RuneQuest-Con (1994), organized in Baltimore, Maryland, by RuneQuest fan David Cheng. Rowe decided to follow it up with RQ-Con 2 (1995) in San Francisco the next year. He and Appelcline also opted to write a LARP, “The Broken Council,” since Gloranthan live-action games had become a staple of RuneQuest conventions in the UK and the US. They received help from Gloranthan fan Stephen Martin — who as it happens was Dave Martin’s brother, proving how small the roleplaying world is.

Everyone involved learned not to simultaneously plan a convention and write a LARP, but nonetheless it all came together on January 13–16, 1995. Kubasak was shanghaied at the last minute to help with LARP prep and to sign books (using Rowe’s name) and everything came off mostly okay. The weekend convention also resulted in the only books that members of the Mafia produced themselves without releasing them through a publisher. There was a pre-con book (1994) and a con book (1995), but the LARP’s The Broken Council Guidebook (1995) was more notable for the roleplaying field; it was the first ever in-depth look at Glorantha’s First Age, written following discussions with Gloranthan creator Greg Stafford. The book was authored by Appelcline, Rowe, and Martin and included artwork by Filios.

Later that year Appelcline produced The RQ-Con 2 Compendium (1995), bringing the RQ-Con 2 experience to a close with LARP reports and seminar transcripts. However that wasn’t the end for Rowe. If the Internet was the main conduit to professional roleplaying work for amateurs in the ‘90s, then fan communities were second. Based primarily on his experience managing RQ-Con 2 — and the connections he made with Chaosium — Eric Rowe was soon hired by the game company as a marketer.

Meanwhile Appelcline had started an electronic newsletter called The Chaosium Digest (1994–2012). It was a weekly or biweekly collection of articles for Chaosium’s games, largely written by Appelcline with help from Rowe, but with contributions from internet subscribers as well. Appelcline hoped it would eventually give him a foot in the door at Chaosium, and that’s exactly what happened.

In short order, Appelcline and Rowe were asked to contribute to a few of Chaosium’s upcoming books: Chronicles of the Awakenings (1995) for Chaosium’s new Nephilim (1994) game and Taint of Madness (1995) for Call of Cthulhu. In the years afterward, Appelcline also edited a few books that he organized himself: the Gamemaster’s Companion (1996) for Nephilim and Tales of Chivalry & Romance (1999) and Tales of Magic & Miracles (1999) for Pendragon — though the last two were delayed for a few years by Chaosium’s financial problems and shifting priorities. As had been the case with other industry connections of the ‘90s, Kubasak and Filios both contributed to these projects.

Ooh, killed by another vegetable.

Shannon Appelcline as GM, Pendragon game

As Appelcline hoped, Chaosium hired him in 1996. He worked for them as a layout artist and editor for two years. Rowe continued his own marketing work during this time, but their paths diverged in 1998 when Chaosium ran into financial problems related to its overprinting of the Mythos CCG (1996). Appelcline, more risk adverse, went back to the computer field, while Rowe took over Chaosium’s mail order arm in exchange for debts owed to him. He then made Wizard’s Attic into a fulfillment house, just in time to take advantage of the d20 explosion.

These histories have told the stories of several gaming groups that impacted the entire industry, and the RuneQuest Mafia is one of them. Through the group’s interest in RuneQuest, Pendragon, and other Chaosium games and through Rowe and Appelcline’s work on RQ-Con 2, Rowe ended up running a company that distributed the products of approximately 80 RPG companies in the early ‘00s. When it crashed, for reasons described in its own mini-history, it took some of those companies with it. Even big companies like Mongoose were affected.

Following the crash of Wizard’s Attic in 2003 and the results of the US presidential election in 2004, Rowe decided to move back to his birthplace in New Zealand, which would result in the groups’ biggest shake-up ever.

Meanwhile, with the coming of the ‘00s, the era of members of the group working together on roleplaying projects was past. Appelcline is the only one who’s continued in the field. He’s run RPGnet since around 2003 and for a while regularly wrote for Chaosium and Gloranthan fanzines. He also contributed to Hero Wars (2000), and authored two Gloranthan elf books: “Oak & Thorn” for Issaries, which was never published, and Elfs: A Guide to the Aldryami (2007) for Mongoose, which was. The fact that a 100,000-word book ended up unpublished due to the vagaries of changing companies and ownerships in the industry led Appelcline to focus on projects he fully owned instead. The first of these was Designers & Dragons (2011, 2014).

Meanwhile, the rest of the Mafia was focusing more on their own professional careers, a general trend for a group that had by now entered its second decade.

Mature Gaming: 1999-Present

There’s a difference between a young gaming group and a mature gaming group. The young group is all about the games, and players might flit in and out of the group at any time. As a gaming group matures it becomes about the people, and the games become the glue that holds them together.

With more than a decade gone by, some of the members of the Mafia were held together by more than that. They’d almost all ended up in the computer industry and as often as not a few of them worked at the same company.

Meanwhile, the group’s social fabric was maturing in another way. John Tomasetti was married in June 1999, Shannon Appelcline in August 2000, Eric Rowe in October 2002, and Dave Pickering in April 2003. This sort of maturation represents another danger to a college group, just as the ending of college days does: though Appelcline and Pickering stayed with the group, Tomasetti faded away after he met his wife, and Rowe would leave for New Zealand just two years after his own wedding.

By 2004, the Mafia was composed of Shannon Appelcline, Eric Fulton, Donald Kubasak, Dave Pickering, Eric Rowe, Kevin Wong, and when circumstances allowed Dave Sweet and Dave Woo. The group was still a healthy size, but it would have been easy for it to disintegrate after Rowe’s departure, because he’d been the central GM of the Mafia for 15 years.

Instead, it kept on. Appelcline stepped up as a regular GM, running games of Elric! (1993), AD&D 1e (1977), D&D 3.5E (2003), Mongoose Traveller (2008), and Pathfinder (2009). Wong had been regularly running since 1997 and he continued on with GURPS, Deadlands: Hell on Earth (1998), and Pendragon campaigns. Kubasak and Fulton also ran a few games of their own.

Though gaming continued, there were changes to both its tone and its frequency. All of the GMs were now more likely to use packaged adventures than the more imaginative and responsive games run for Ars Magica and RuneQuest in days past, and the frequency of the games decreased: though there were sometimes still two games on a Saturday, not everyone stayed for both sessions, and at other times there weren’t games for weeks.

I can’t believe how adverse to work you are in this imaginary world.

Dave Sweet, Pathfinder game

Nevertheless, the group started to grow again. Kevin Wong’s younger brother, Christopher Wong, became a regular participant and even GMed some D&D 4E (2008) games; he was soon joined by his fiancé Corina Borroel. Meanwhile, Donald Kubasak brought in his girlfriend Mary Seabrook, who briefly ran The Dresden Files Roleplaying Game (2010). Suddenly a group that had been shrinking since the late ‘90s topped out at an almost unmanageable size of 10! These new attendees also brought the first paired gamer weddings: Donald and Mary were married in January 2010 and then Christopher and Corina were married that October.

A gaming group grown mature had also become family. They played together, they worked together, and they even vacationed together on occasion. Dave Sweet, Kevin Wong, Christopher Wong, and Chris Van Horn all drove in a van from California to Milwaukee to attend the 2002 Gen Con Game Fair together, where they were met by Dave Woo (who flew). Several members of the group also attended DaveCon in Apple Valley, California, in 2004, a convention just for the Mafia. Some visited Rowe in New Zealand in 2009 for DaveCon II: Go’n Kiwi, while another Gen Con trip happened in 2012.

Unfortunately the 2000s also brought one tragedy: Chris Van Horn passed away in December 2008. He hadn’t been a regular member of the Mafia for years, but he was still missed and mourned.

Today, the RuneQuest Mafia is surprisingly spry for a group that’s 25 years old. Appelcline is finishing a four-year run of Pathfinder’s Kingmaker campaign — though he’s been claiming that it’s almost over for a year. His recent campaigns have all been run at EndGame, a game store in Oakland, California, that’s also the nexus of Evil Hat Production’s West Coast presence. Meanwhile Wong is near the start of Pendragon’s Great Campaign.

Sometimes members of the Mafia disappear for a month or a year or two due to any number of life reasons. However, they always seem to return, drawn back by the inexorable schedules of gaming.

Appendix: Tales of the Mafia

Alex & The Character Sheet. During one of Eric Rowe’s ErzoQuest games, Alex Purl found his character mortally wounded. Again. In frustration he ripped his character sheet up. However within the next round, a healer got to Alex’s character and saved his life. Looking at his shredded character sheet, Alex called for scotch tape.

Don & The Chair. In an Ars Magica game, Don Petrovich found his new character, Angus, killed. He hadn’t really had a chance to play the character, so he just erased the name, wrote something new, and continued on. One of the other players at the table thought this funny, and kept calling the “new” character “Angus the Younger.” Don said, “Don’t do that,” but the jokester continued. Don said, “No, really, don’t do that.” When the other player called him “Angus the Younger” one more time, Don picked up a chair and threw it. But he missed his taunter and hit someone else instead!

Dave S. & The Horse. Shannon Appelcline occasionally turned his Pendragon games over to the rest of the troupe to run, and Dave Sweet decided to give it a try. The players insisted on toiling through cold and snow, well past where they were supposed to go, and Dave kept making them roll their Energetic trait. When a character failed his roll, the personality trait dropped. No one was too concerned, though Dave kept saying, “You feel cold.” Then Mike Lee’s Energetic dropped to zero and Dave said, “You freeze to death on your horse.” The group was flabbergasted.

Clayton & The Faeries. Clayton Springer was one of many players who joined the Mafia just for Ars Magica games. Like many such casual attendees, he didn’t really understand the mindset of the group. One day he was running a game where the players met a group of faeries. Clayton clearly expected everyone to talk and so was unconcerned when Dave Pickering kept asking the faeries to crowd closer and closer together. Dave finally confirmed that the faeries were in a very tight group in front of him and said, “I Arc of Fiery Ribbon them.” In Ars Magica, faeries are magical power personified (or as we say, “vis on the hoof”). The faeries died. The GM was flabbergasted.

Dave S. & The Pit. During a Star Wars game, Dave Sweet embraced the spirit of roleplaying when his Wookiee warned the rest of the party about a pit he’d discovered. There was of course a language problem, so Dave simply shouted, “Woowworrah!!” The rest of the players acted like they had no idea what Dave was talking about — but for the rest of the campaign whenever Dave’s Wookiee spoke they said, “Watch out! There’s a pit!”

Kevin & The Car. When a few members of the gaming group had too much to drink one evening, Kevin offered to drive them home. Unfortunately, he was driving a stick shift, and he wasn’t any good at it. At a stoplight, Kevin accidentally rolled the car back into the vehicle behind him. And then that vehicle’s police siren came on. Kevin had to explain to the officer how he was the sober one, driving everyone else home.

That’s it for the three Platinum-Dragon-sponsored articles. There’s more material that came out of the Kickstarter (and all of this in a nicer format) in the actual Platinum Appendix. Of course, the complete Designers & Dragons series is available for purchase as well.

If you’d like to see my current historical writing, visit D&D Classics every week. I’ll also be returning to this column with new articles, hopefully on a bimonthly basis in 2016, starting with a look at the year in review on 1/1/16.