This article is part of a semi-monthly column on the history of roleplaying, one game company at a time. The intent is to cover one large RPG company each month, then a smaller, but related one. Chaosium is our second big company, and also one of the oldest RPG companies still around. It’s additionally a company that I worked at from 1996-1998, giving me a bit of personal insight.

This article was originally published as A Brief History of Game #3 on RPGnet. Its publication preceded the publication of the original Designers & Dragons (2011). A more up to date version of this history can be found in Designers & Dragons: The 70s.

At the start of 1975 there was only one roleplaying game in existence, Dungeons & Dragons, and thus it isn’t much of a surprise that Chaosium, or “The Chaosium” was it was then called, was founded instead as a board game company to publish Greg Stafford’s board game White Bear & Red Moon.

Board Game Beginnings: 1975-1981

Stafford had been writing about the world of Glorantha since freshman college days in 1966. However after a particularly rude rejection letter from a fantasy fanzine, Stafford instead decided to publish the first entry into Glorantha as a “do-it-yourself” novel. This was the game White Bear & Red Moon. He hadn’t intended to publish that himself either, but after he sold it to three different companies, each of which went out of business (or failed to get off the ground), he finally decided to publish it on his own, a decision guided by an auspicious reading of Tarot cards.

And thus The Chaosium was born. White Bear & Red Moon was published in 1975.

From 1975-1981 Chaosium published 11 different board games, some of them in multiple editions. For the most part these games exist outside of our history of roleplaying, with a few exceptions:

- Glorantha continued its early existence through the publication of Nomad Gods (1975). A third game in the series called Masters of Luck & Death was planned, but never published.

- Elric (1977), by Greg Stafford, was a wargame based upon a license from Michael Moorcock, and as we’ll see it was a license that later helped Chaosium to expand their gaming lines.

- Greg Stafford’s King Arthur’s Knights (1978) was part of the second wave of adventure games (following in the footsteps of TSR’s Dungeon!). Adventure games bring roleplaying ideas, like singular characters who can improve, to a board gaming paradigm. We’ll meet the genre again in 1984 when Chaosium released their (perhaps) most notable board game.

The rest of Chaosium’s early board games were mostly wargames, some light and some heavy, following in the footsteps of early pioneers like Avalon Hill and SPI. However, they came to a halt in 1981 because of a new force that had building at Chaosium for four years.

Roleplaying.

Roleplaying Beginnings: 1977-1981

Years earlier, by strange chance, Greg Stafford received what appears to be the first copy of Dungeons & Dragons that was ever sold. An ex-partner of his who lived in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin was picking up catalogues from a printer and there he ran into a young man who would turn out to be Gary Gygax, who was picking up the first print of Dungeons & Dragons. Stafford’s partner knew that Stafford was working on a fantasy game too, and so he purchased a copy of Dungeons & Dragons from Gygax, straight off the press, and mailed it to Stafford.

Not long after Stafford decided he wanted Glorantha published as an RPG too. A first attempt was made by Hendrik Jan Pfeiffer, Art Turney, and Ray Turney who were planning on publishing White Bear & Red Moon as a D&D supplement, but Stafford was more interested in an original RPG for the world of Glorantha. Thus when he met Steve Perrin, Steve Henderson, and Warren James at a Greyhaven party, that was what they began to plan. (Ray Turney would later join this new team of developers.) The RuneQuest system was under development.

1977 was the year that Chaosium began publishing RPGs. It was an era when everyone was publishing supplements for the original Dungeons & Dragons game. Even though Stafford had decided to avoid this route for Glorantha, he was still happy to publish Steve Perrin & Jeff Pimper’s All the Worlds’ Monsters, a D&D-based monster manual.

Though AD&D got their own Monster Manual out later the same year, the Worlds’ Monsters supplements put Chaosium on the map as a publisher of RPGs. It was a fledgling industry that then consisted of just TSR, Flying Buffalo, GDW, Judges Guild, Fantasy Games Unlimited, Metagaming Concepts, and a few smaller companies–Chaosium may well be one of only two survivors from this dawn of roleplaying.

That same year Chaosium almost published another notable RPG: The Arduin Grimoire. Dave Hargrave submitted the manuscript to Chaosium, but it was ultimately rejected as too derivative of D&D, and not a full system on its own. Though Chaosium was happy to publish supplemental material for D&D, when publishing full games they wanted unique systems all their own.

Beginning in 1978 Chaosium would manage exactly that when they began publishing their own Basic Roleplaying Games starting with RuneQuest, which we’ll return to momentarily, but until 1981 they remained a real industry player as well.

In 1979 they started publication of a general roleplaying magazine called Different Worlds, overseen by Chaosium’s second employee, Tadashi Ehara.

Then in 1981 Chaosium published a product of a scope not seen before in the industry, and probably not seen again until Wizards of the Coast’s The Primal Order (1992). It was Thieves’ World (1981), a roleplaying supplement based on Robert Asprin’s fiction series of the same name.

Thieves’ Worlds was particularly notable because it was the earliest massively multistatted RPG supplement, with rules for AD&D, Adventures in Fantasy, Chivalry & Sorcery, DragonQuest, D&D, The Fantasy Trip, RuneQuest, Traveller, and Tunnels & Trolls. The credits page is a pretty amazing who’s who of the period’s gaming personalities, including Dave Arneson, Eric Goldberg, Marc Miller, Steve Perrin, Lawrence Schick, Greg Stafford, and Ken St. Andre.

Thieves’ Worlds was also one of the few early RPG product that was able to legally use TSR’s trademarks for their fantasy systems. This came about due to TSR’s unauthorized uses of the Melnibonean and Cthulhu mythos in their 1980 Deities & Demigods; both trademarks were held by Chaosium for games that they were then in the process of developing. An exchange was arranged: Chaosium got the rights to use the TSR trademarks in Thieves’ World and in exchange TSR was allowed to continuing using the Mythos … which they ironically dropped almost immediately due to fears of satanism which were then heating up in the industry.

1981, however, marked the end of Chaosium’s early era of producing generic supplements of use for other games. They’d briefly revive the idea five years later when they published Midkemia Press’ Carse (1986), Cities (1986), and Tulan of The Isles (1987), but for the most part Chaosium’s time as a supporter of other publishers was done, because they’d developed a successful product of their own: RuneQuest.

The Birth of BRP: 1978-1982

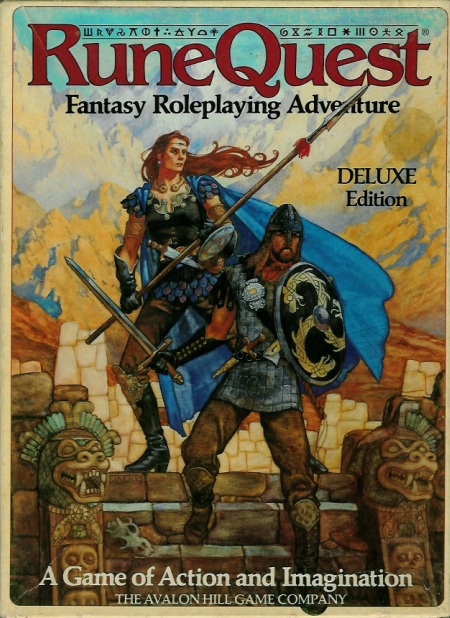

In 1978, Chaosium’s two core businesses–roleplaying games and Gloranthan board games–naturally merged when Steve Perrin led the design team which created RuneQuest, a RPG set in Greg Stafford’s world of Glorantha. RuneQuest followed upon the heels of the first wave of fantasy RPG designs–including Dungeons & Dragons, Empire of the Petal Throne, Tunnels & Trolls, Melee, and Chivalry & Sorcery. In turn it would be quite influential on second-wave RPG designs like Dragonquest, The Fantasy Trip, and Rolemaster. Among its contributions to the industry:

- It was the first game to introduce a fully skill-based character system. Traveller had previously introduced skills to roleplaying, but with two major caveats. First, the skill system was ultimately confined during creation by a character “class”, and second, there was no experience system. RuneQuest resolved both of these issues.

- It was one of the earliest deeply detailed fantasy world. This was an emerging trend in roleplaying, with other early contenders including TSR’s Empire of the Petal Throne (1975), Judges Guild’s City-State of the Invincible Overlord (1976), and GDW’s Traveller Imperium, which really started showing up with their 1979 publication of The Journal of the Travellers’ Aid Society.

- It was the earliest serious look at religion in RPGs. Before that clerics had been present, but their religion was mostly glossed. Even when TSR put out Deities & Demigods (1980), they treated them gods more as monsters than as an important cultural force.

RuneQuest was successfully published by Chaosium through a second edition in 1979, a series of about two dozen supplements published through 1983, and fourteen issues of a RuneQuest magazine called Wyrm’s Footnotes. Though some of their early supplements were very early-era dungeon crawls and stat books, in 1982 and 1983 Chaosium published some of the best supplements to date in the RPG industry, including one excellent set of linked scenarios (Borderlands, 1982), two superb city/wildland background books (Pavis and Big Rubble, 1983), and what could well be seen as one of the earliest splat-books (Trollpak, 1983), which was written by Greg Stafford and Sandy Petersen, the latter fresh from a biology degree (and it shows!). Most of these RuneQuest 2 books remain in print today from Moon Design Publications.

In 1980 Chaosium then expanded their RuneQuest system in a unique way. They published a cut-down version of the RQ rules called Basic Role-Playing. By extracting their core game engine they created the first generic roleplaying system, two years before the Hero System expanded beyond Champions and six years before The Fantasy Trip became GURPS. In 1981 Chaosium took the next step by releasing two more game system with BRP at their cores.

Stormbringer, another fantasy RPG, was the first. It actually preceded the publication of Thieves’ World the same year and thus was Chaosium’s first licensed roleplaying game. Chaosium had originally obtained the rights to the Elric books for “gaming” in order to produce the 1977 Elric board game, and after the success of RuneQuest they decided to build a BRP RPG on the license as well.

It wasn’t the first licensed RPG ever–that was SPI’s Dallas (1980)–but it may have been the first licensed RPG that was actually supported. An edition of the game is still in print today, 25 years later, though only about 20 supplements have been published in that timeframe. And Stormbringer was just the start: the idea of licensing worlds is a trend that Chaosium has successfully managed throughout their history.

Stormbringer was soon followed by (and eclipsed by) Call of Cthulhu, the first horror roleplaying game, designed by Sandy Petersen, licensed by Arkham House, and based on H.P. Lovecraft’s stories. Call of Cthulhu excelled in theming, even moreso than RuneQuest before it, and thus became a icon of the roleplaying world. Twenty-five years later, it’s the entire core of Chaosium’s business and it remained the top horror RPG for over a decade, until it was overshadowed by White Wolf’s World of Darkness line in the 1990s.

In the modern roleplaying world, we take some things entirely for granted, and one of those is player aids. TSR had played with the idea a bit in their S-series of modules, beginning with Tomb of Horrors (1978), which included a book of pictures to show to players. Chaosium took the next step with the first Call of Cthulhu supplement, Shadows of Yog-Sothoth (1982), which had an 8-page centerfold full of textual player information sheets, meant to be handed out to the players. These were actual clues which players could puzzle out, taking the mysteries of this first horror game up to the next level. Today textual player info is much more common, and it ultimately derives from this book.

BRP Growth & Change: 1982-1984

With the success of Stormbringer and Call of Cthulhu in 1981, Chaosium decided to continue the trend of expanding the BRP system into new genres.

Worlds of Wonder (1982) appeared next. It presented three worlds of adventure: fantasy, science fiction, and super hero. Its Superworld (1983) would become its own book. Meanwhile over in Sweden Worlds of Wonder‘s Magicworld became its own game too, Drakar Och Demoner (1982). It’s notable because, over the next decade, it would be the best-selling Swedish RPG, with over 100,000 copies sold. However from the third edition (1985) onward, it started deviating largely from its BRP roots, even throwing out the d100 for a d20.

Back in the United States two more licensed products soon joined the BRP lineup: Elfquest (1984) and Ringworld (1984).

At the same time Chaosium was making massive changes in RuneQuest. This came about, ironically, due to changes in Chaosium’s board game line. The company had stopped publishing new board games in 1981. Stafford would later recount that they took twice as much time to produce and twice as money to print and sold half as much. (Sadly, a reverse of the industry today.) However, Chaosium didn’t want their board games to die entirely. So, they went to Avalon Hill and arranged a deal for Avalon Hill to produce new versions of White Bear & Red Moon (renamed Dragon Pass) and the Elric board game.

However, Avalon Hill was then also getting ready to roll out their own roleplaying line and they were interested in RuneQuest. Chaosium wouldn’t sell it, but did agree to a license, It seemed like a great plan and a way to bring RuneQuest up to the next level: Avalon Hill would do manufacturing and marketing while Chaosium would do acquisitions, design, development, and layout. Each company played to its strengths.

Chaosium held the rights to Glorantha a bit closer to their vest, so in 1984 when the new third edition of RuneQuest came out, it was instead based in a “Fantasy Earth”. It turns out that was ultimately a good decision for the future of Glorantha, because there were problems with the partnership from the start, when Avalon Hill opted out of including the designers’ credits on the front of the box. Chaosium’s “dream” deal would turn worse as the years went on.

Arkham Horror & Pendragon: 1984-1985

In the next couple of years, Chaosium would publish two more very innovative projects.

The first was Richard Launius’ Arkham Horror (1984). Though Chaosium had previously stopped their board game production, this Call of Cthulhu-based board game was sufficiently interesting to make them reconsider their decision.

It would break new ground:

- Most notably, it was perhaps the earliest cooperative game, allowing players to work together to defeat a common foe controlled by the game system.

- It was also part of a 1980s resurgence of adventure games that would include Talisman (1983) and Milton Bradley’s HeroQuest (1989). Even moreso than the 1970s adventure games which had included Chaosium’s King Arthur’s Knights, Arkham Horror really modeled the RPG experience.

By today’s standards, the original Arkham Horror is a pretty creaky game, but Fantasy Flight Games has recently down a great job of reviving it and incorporating 20+ years of industry growth and new game design know-how.

Even more important to the RPG industry was the release of Greg Stafford’s King Arthur Pendragon (1985). It’s a game that Greg Stafford regularly calls his masterpiece. Like RuneQuest before it, Pendragon introduced quite a few new ideas to the industry:

- There was a system for personality traits and passions which could control a character. Call of Cthulhu had an insanity system, but beyond that there were almost no models for mental behavior of this sort prior to Pendragon.

- Building on these personality traits, the game system was deeply tied to the game setting, and still serves as an example of how RPGs can be improved by having such a tie, rather than using a more generic system.

- Pendragon (and its earliest supplements) contained an outline for an entire (80-year) campaign chronology, that went far beyond a setting like RuneQuest‘s which was poised on the edge of a conflict that never quite emerged and even beyond the slow move forward of Traveller‘s TNS system.

- There was an emphasis on something beyond the individual characters, here a family tree, from which the player would inhabit several members over the course of a campaign.

Pendragon was the only Chaosium RPG ever released that wasn’t truly BRP based. There are numerous similarities, but also a lot of unique systems–and a d20 rather a d100. It’s also one of the earliest instances of the “storytelling” branch of roleplaying games, which were later developed further by Jonathan Tweet, Robin Laws, and others. Pendragon placed storytelling and epic plot above individual characters.

In 1985 Chaosium seemed poised on the edge of great success. They had a half-dozen game lines, including the innovative & exciting RuneQuest and King Arthur Pendragon. Call of Cthulhu was already producing classics like Masks of Nyarlathotep (1984). Chaosium had licensed off their best board games, and despite initial problems, Avalon Hill had put out 6 boxes of RuneQuest material including a return to Glorantha with Gods of Glorantha (1985). Arkham Horror was also on its way to becoming a cult classic.

Within a year this success would turn, and Chaosium would be teetering on the edge of bankruptcy.

The First Downturn: 1985-1988

The seeds for Chaosium’s first downturn had been planted in 1983 with the licensing of RuneQuest. The hope had been that Avalon Hill would massively market the game in a way that Chaosium had never been able to, thus bringing it up to the next level. The reality was quite different. If RuneQuest sales changed it wasn’t by much. This was a big problem for Chaosium.

Previously, RuneQuest sales had been a notable part of Chaosium’s cash flow. Now instead of receiving 40% of sales from distributors they were instead receiving a much smaller portion of sales as royalties. Worse, they were diverting considerable creative resources toward Avalon Hill’s RuneQuest, and thus weren’t developing their own lines. If Avalon Hill had been able to double or triple sales, everything would have worked out, but without that Chaosium started heading toward serious fiscal problems.

The first sign of the impending problems was seen in 1985. Superworld and Ringworld, which were each still being published in 1984, ceased production that year (admittedly, also amidst the release of Pendragon, and continued support for Call of Cthulhu, Stormbringer, and even Elfquest).

The downturn becomes more obvious in 1986. Tadashi Ehari left Chaosium early that year, taking with him Different Worlds magazine. The same year Chaosium published their last ever boxed game, Hawkmoon. Because of their worsening finances Chaosium no longer could afford to hire labor to collate their games. Much of their staff had been laid off, and if Chaosium were an ordinary corporation, they probably would have folded, but because the owners of Chaosium truly loved roleplaying games, not just running a business, they held on, doing everything themselves.

Unfortunately, things wouldn’t get better for a while. In 1984 an explosion had occurred in the black & white comic market thanks to speculators becoming interested in low-print-run comics like Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and Elfquest (which Chaosium of course held a license for). By late 1986 and early 1987 that bubble had burst, much like the CCG and d20 bubbles later would. Some retailers went out of business as a result, and then some distributors too. Since the comic and roleplaying markets are adjacent this inevitably saddled RPG companies with some unpaid bills and some lost futures. It was another disaster that Chaosium, already in bad shape, did not need.

Looking at publication records it appears that the Chaosium downward spiral reached its nadir in 1988 and 1989. In 1988 Chaosium ceased the publication of every one of their lines except Call of Cthulhu, and published very little of even Cthulhu that year. In 1989 Elfquest would reappear (for one final publication), but it would be 1990 before Stormbringer and Pendragon were supported again (each with a new edition).

A New RPG Golden Age: 1986-1992

Despite the downturn of the 1980s, the time during and after this hardship would still be a golden time for Chaosium publications. With just one exception Chaosium would focus on their existing and most successful lines during this period.

The exception was Prince Valiant (1989). It was a one-off publication by Greg Stafford. Some of its highlights are: a strong storytelling basis; the use of a coin as a randomizer; a one-page game system; matched player and character reward systems; and an early troupe style system which allowed players to become storytellers for brief scenes. If it had received more attention, it probably would have become a pivotal game, as important for its new roleplaying ideas as other releases of the time like Ars Magica (1987) and Vampire: The Masquerade (1991).

The rest of Chaosium’s publications from 1986-1992 supported their existing lines.

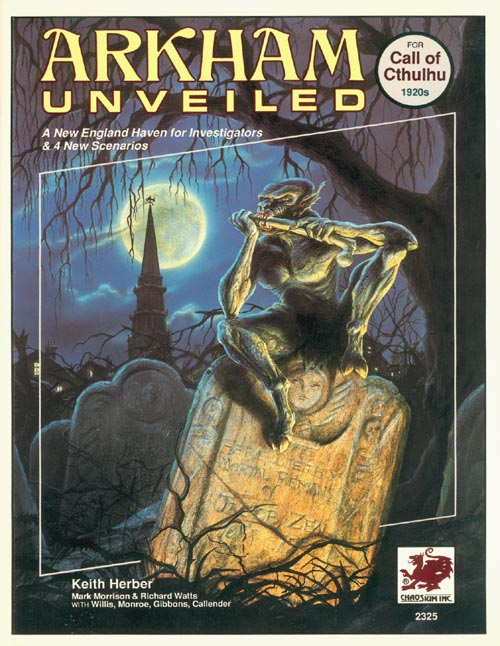

Call of Cthulhu saw many solid supplements published during this time. Chaosium flexed its BRP muscles by extending the game into the Victorian age (Cthulhu by Gaslight, 1986), a fantasy world (H.P. Lovecraft’s Dreamlands, 1986), and the modern day (Cthulhu Now, 1987). Immediately after the downturn Chaosium published a new fourth edition of Call of Cthulhu (1989), and then began its very successful set of Keith Herber edited Lovecraftian background books with Arkham Unveiled (1990). The series would run through Escape from Innsmouth (1992).

Pendragon’s most important publication before the crash was The Pendragon Campaign (1985), which offered the first hint of the game’s massive campaign chronology. Other than that the first edition of Pendragon was supported only by light adventures. Following the downturn a third edition of King Arthur Pendragon (1990) was published, then Chaosium released The Boy King (1991), fully outlining the first half of that 80-year campaign. This would mark the height of the Pendragon line which continued through numerous sourcebooks detailing the lands and peoples of Britain–though only a book a year was published after 1992.

(Curiously, there is no second edition of Pendragon. It was planned as a boxed set, but then the downturn and the move away from boxes nixed it before it went to press.)

Stormbringer was only lightly supported up to 1985, but with the publication of a second edition that year, the line took off with a total of 9 publications from 1985-1987, including a second game, Hawkmoon (1986). Unfortunately these early supplements consist mainly of dungeon delves, puzzles, and other early-era RPG adventures. The line didn’t really mature until 1990. Following the two-year hiatus surrounding the downturn, a fourth edition of the rulebook was produced, and then first Keith Herber and later Mark Morrison started putting out thick, well-written books of background and adventures.

Meanwhile, Chaosium worked with Avalon Hill to support RuneQuest up through 1989, when the relationship really began to fall apart just as Chaosium was getting back on its feet. As a result Avalon Hill would first publish non-Glorantha products, then drop the line entirely for two years. When RuneQuest returned in 1992 under editor Ken Rolston, Chaosium would have little more to do with the line (and indeed was already working on Gloranthan projects of their own).

Fiction Lines: 1992-1997

With the downturn behind them, in late 1992 Chaosium struck out in an entirely new area of publication: fiction. King of Sartar (1992) was Chaosium return to Glorantha and also the first Chaosium work of fiction, but it was clearly an entirely niche product. Penelope Love’s Castle of Eyes (1992) was a curious second choice for the fiction line, as it was “a novel of dark fantasy” with no connection to any game line.

In the meantime, however, Greg Stafford had attended NecronomiCon, a Lovecraftian convention held in Massachusetts, and had come to realize that the Lovecraft community of the early 1990s was made up of two classes of people: those who had come to Lovecraft through the fiction and those who had come to it through Chaosium’s game, Call of Cthulhu. There was little overlap. The realization that most of the Cthulhu players hadn’t actually read the fiction caused Chaosium to begin a line of Cthulhu fiction.

Most of the early Cthulhu books were overseen by Robert M. Price, the editor of the long running ‘zine Crypt of Cthulhu. His first book was The Hastur Cycle (1993), a collection of short stories which traced the development of a single Lovecraftian element, here Hastur. It was followed by Mysteries of the Worm (1993), a collection of Robert Bloch’s Mythos fiction. Price’s encyclopedic understanding of the Mythos and its authors would make these and many other “Cthulhu Cycle” books a success. Meanwhile Cthulhu’s Heirs (1994) was a different type of book, a new collection of Mythos fiction. Thematic collections, authorial collections, and new fiction collections would comprise most of the Cthulhu fiction publications for the next 13 years.

Publishing literary collections was an excellent choice for Chaosium because so many of their games were themselves based on fiction, and there was probably no better choice than Lovecraftian fiction which had a huge pool of stories to draw from, many of them well out-of-print. However, Chaosium also faced a core problem: though they were publishing collections that might have been well received by the mass market, they also faced the stigma of being a gaming publisher, and thus having their fiction collections relegated to that niche. This was particularly a problem in specialty science-fiction, fantasy, and horror book stores, who were wary of stocking the books due to the gaming connection. As a result the “Call of Cthulhu Fiction” label would slowly shrink on Chaosium’s books in the years to come. It went from a top cover position in 1993 to a smaller, bottom cover position in 1995, and seems to have been entirely removed from the cover in the very recent Arkham Tales (2006).

Despite the stigma of being published by a game company, the Call of Cthulhu fiction line was successful. By 1995 the early black & white covers were being replaced with photographic constructs by H.E. Fassl, and another few years after that the fiction was selling at rates better than most of the game books themselves.

In 1997 Chaosium introduced a second line of fiction, for Pendragon. If anything this genre offered up even more possibilities to reprint out-of-print genre classics, since the genre dated back hundreds of years. The line led off with The Arthurian Companion (1997), which Chaosium had published many years before as a gamebook, and the short novel Percival and the Presence of God (1997).

Though the Call of Cthulhu fiction line continues today, the Pendragon fiction line would rather abruptly switch hands in 1997 as the result of changes ultimately caused by Chaosium’s other gaming interests.

Another Gaming Boom & Bust: 1993-1998

At the same time as it was entering the fiction field, Chaosium also started working on new roleplaying systems for the first time in almost a decade.

The first was Elric! (1993), which was a totally new system meant to replace Stormbringer. The reasons for the change aren’t entirely clear, but the new system down-played demons and up-played common magic, perhaps making it more accessible, particularly in Middle America.

Then in 1994 Chaosium put out Nephilim, a modern occult game system originally developed by their French licensee, Multisim. This was part of the first wave of foreign-language RPGs translated into English, following Kult (1993) and Mutant Chronicles (1993), and was the first French RPG translated into English. Later other games, most notably Steve Jackson’s In Nomine (1997), would follow.

Unfortunately, Nephilim would stand as an example of how not to push out a roleplaying line. It was rushed out for GenCon that year (as roleplaying products often are), and that may well have killed the line. The rulebook was sloppy. The magic system was wonderfully thematic, but required complex calculations. Further, because of the rush job, Chaosium wasn’t ready to support the line afterward (another cardinal error of roleplaying releases) and so in 1994 the only supplements published were a gamemaster screen and a pad of character sheets. The first real supplement followed the game release by some 8 months.

Worse, Nephilim wasn’t an easy game to figure out, and the rulebook just didn’t offer sufficient guidelines for what a campaign might look like. The lack of adventures just made this worse. Chaosium would only publish one adventure book for Nephilim (Serpent Moon, 1995), a full year after the original game release. I personally tried to help address the issue with a Nephilim Gamemaster’s Companion (1996), which devoted almost 40 pages to Nephilim campaigns, but with its release almost two years after the original game, it was too little too late. The line would close down in 1997, three years after it got started amidst another rough spot in Chaosium’s finances (and one that I witnessed first hand while working there).

In the meantime there was a new fad in town, collectible card games, and everyone was jumping on the bandwagon. Chaosium did so in 1996 with Mythos, a Call of Cthulhu CCG that was actually quite innovative in its emphasis on stories told through the cards (rather than just attacking your opponent, which was the basis of most CCGs). The CCG industry was already starting its downward trend by 1996, but there was still room for an interesting & innovative design, and Mythos was. The initial releases did gangbusters, allowing for a period of dramatic expansion at Chaosium.

Unfortunately, the good fortune turned around almost immediately with the release of Mythos Standard Game Set (1996). It was a non-collectible set of two decks, meant to be an entry-point to the game. However, it was a non-collectible game printed at collectible card levels. Years later there were still pallets of the game in the warehouse, and more immediately retailers were now newly wary of Mythos sales levels. Expansions for The Dreamlands (1997) and New Aeon (1997) trickled out over the next couple of years, but then Chaosium permanently got out of the CCG business.

CCG losses usually run at a scale much higher than RPG losses. Hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of inventory were tied up on the warehouse floor and the result was devastating for Chaosium. Most of the staff was let go. When I left in late 1998 there was no one remaining who was actually taking a paycheck. Again, Chaosium responded by shutting down several of its line, this time Pendragon, Elric!, Nephilim, and Mythos itself. By 1997, each one had ceased publication, and Chaosium had once more cut back to being solely a Call of Cthulhu publisher.

The Chaosium Split: 1997-2000

As a result of this second major downturn for Chaosium, the company actually split apart, with three debtors each gaining some of the company’s rights while Chaosium continued on with Call of Cthulhu.

Green Knight Publications was the first. Peter Corless gained the rights to Pendragon, including the fiction line, as the result of a defaulted loan. Chaosium’s last ever Pendragon book was the late 1997 reprint of The Boy King while Green Knight would get off the ground with 1998’s Pendragon fiction novel, Arthur, the Bear of Britain (a book that I’d actually laid out for publication by Chaosium before the rights change). Green Knight will be the topic of A Brief History #5.

Issaries was the second. In the years surrounding the Mythos releases Greg Stafford had been finding a new interest in Glorantha, separate from RuneQuest. He’d begun publishing “unfinished works” about Glorantha in 1994 (at RuneQuest-Con 1), and had since commissioned a new roleplaying game from Robin Laws. With this newest Chaosium downturn, Greg decided in 1998 to part ways from the company he’d founded, taking all Gloranthan rights with him. He’d later use them to form Issaries Inc., which will be the topic of A Brief History #4.

Wizard’s Attic was the third Chaosium spin-off, and they’d have the largest effect of any of the new companies on roleplaying in the early 21st century. Wizard’s Attic had started off as a mailorder arm of Chaosium intended to sell mostly Cthulhu-related goodies like t-shirts, buttons, and bumper stickers. Around 1998 it was given to Chaosium marketer Eric Rowe, again as a result of unpaid debts. Using his knowledge of the book trade, developed from selling Chaosium’s fiction line, Rowe turned Wizard’s Attic into a full fulfillment house that did warehousing, marketing, and sales for dozens of RPG companies.

Within a couple of years Wizard’s Attic was doing considerably more business than its former parent company, and it ended up renting new warehouse and office space in Oakland that was used by Chaosium, Green Knight, and Issaries. Unfortunately this success was short-lived, as we’ll see shortly.

Modern Chaosium & The Third Downturn: 1999-2003

With the foundation of Issaries, Greg Stafford had officially left the company that he had created 25 years before. Long-time Chaosium employee and part owner Charlie Krank stepped up as the new president of Chaosium. For the next several years, through the split and into the 21st century, Chaosium mainly treaded water, mostly working on their single surviving product line, Call of Cthulhu.

Though times were bad, Chaosium was still able to put out some high-quality products, mainly thanks to loans from friends paying for printing. This included the well-received Beyond the Mountains of Madness (1999), at 440 pages one of the largest roleplaying campaigns ever published, and a special pseudo-leatherbound twentieth-anniversary edition of Call of Cthulhu (2001).

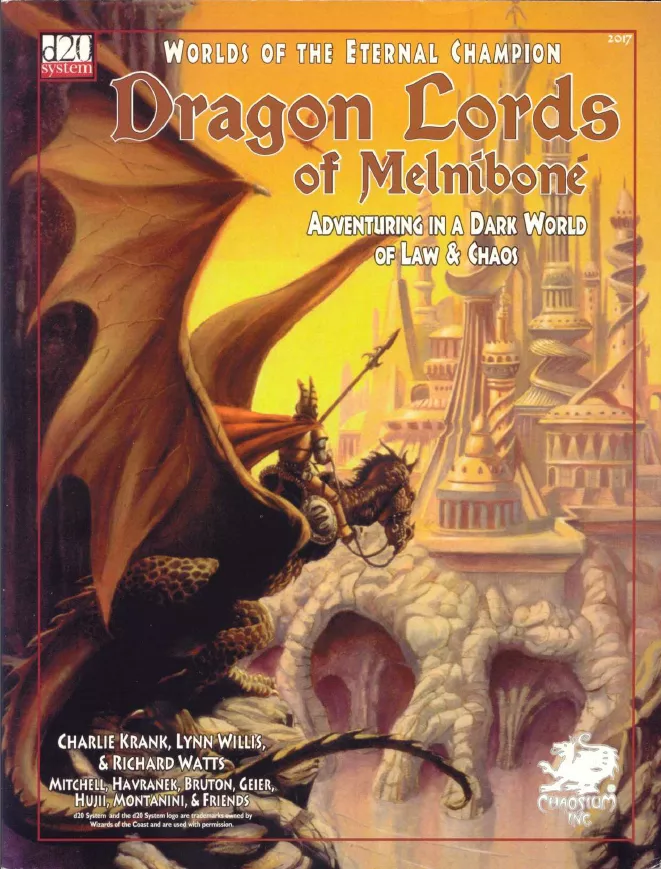

Chaosium also participated in the d20 explosion, though in a fairly minimum way. They rereleased Elric! under the Stormbringer (2001) name, and also released a d20 version of the game called Dragon Lords of Melnibone (2001). They supported the latter with a few adventures, but pretty clearly the real intent was to draw people into the fold of BRP.

Meanwhile, Chaosium licensed Wizards of the Coast to do a d20 conversion of Call of Cthulhu (2002). They supported this line themselves with new editions of their classic Lovecraft Country books, now featuring dual stats. The dual-statted books again showed the desire to draw people into BRP, rather then trying to build d20 as its own business, and this likely protected Chaosium from the d20 crash. A new d20 campaign background, Pulp Cthulhu, was originally planned for 2003, but has been delayed ever since. In 2005 Chaosium announced that it would no longer feature d20 stats, pretty much sounding the death knell of their d20 experiment.

Though Chaosium was somewhat insulated, the d20 crash did catch Wizard’s Attic, who by this time was selling all of Chaosium’s products and renting them their warehouse and office space. The d20 crash combined with Wizard’s Attic’s existing problems related to changes in business practices and bad accounting and would eventually knock them out of business. Chaosium, by now starting to recover a little bit from their second downturn of 1997-1998 was set notably back. They’d end up leaving the Berkeley/Oakland area for the first time in their history and reestablishing the company in Hayward, California.

The Last Few Years: 2003-2006

In the last couple of years, things have started to look up for Chaosium. Relatively few books are being produced, but with more interesting content than has been seen in quite some time, and with considerably more professional layout. To date, Chaosium’s official production remains entirely limited to Call of Cthulhu although word of a new “Deluxe BRP” book has occasionally been heard.

In 2003 Chaosium also started publishing semi-professional monographs, in the spirit of Greg Stafford’s “unfinished works”. Many of these are books written and laid out by fans, with various levels of professionalism. Generally, these monographs seem directed toward the areas that no longer sell well enough to support actual publications. The line has thus included many Call of Cthulhu adventures as well as a few supplements for Stormbringer.

More recently Chaosium published a new standalone Lovecraftian game, Cthulhu Dark Ages (2004), based on the Germanic Cthulhu 1000AD. It marks the first notable expansion of Cthulhu into a new setting since the heady days of 1986 and 1987. Pulp Cthulhu (if it ever comes out) is now intended to be a new standalone game in this same style. Other new settings, including Cthulhu Invictus (2004), set in ancient Rome, Cthulhu Rising (2005), a SF near future, and End Time (2004), a post-apocalyptic SF game, have appeared through the Chaosium monographs. This is clearly a lot of interest in Lovecraftian stories told in a variety of settings.

At this point Chaosium seems pretty solid in their Call of Cthulhu publications, though semi-professional monographs massively outnumber the several professional publications they’re able to put out each year. Further the company appears to rest entirely on that 1981 line. They haven’t had any new RPG systems since 1994’s abortive Nephilim, and no successful new game lines since 1985’s Pendragon. The company is currently run by Charlie Krank, who have been with the company for decades. However, for Chaosium to last more than another decade, it really needs to do more than just retread past glories.

But than the same could be said for the RPG industry as a whole.

For more of this story, read Designers & Dragons: The ’70s and “Chaosium Next: 1997-Present”.

Thanks to Greg Stafford for his comments, corrections, and additions to this article. Also, thanks to James Lowder for thoughts on the role of fiction in Chaosium’s history. And thanks to Donald Reents for pointing out the Swedish Drakar och Demoner. Other information is drawn from Starry Wisdom magazine, Greg Stafford’s discussions at the Acaeum, my own long-time interest in Chaosium, and my experiences working at Chaosium.